While Largely Apolitical Historically, Oscar Speeches Have Grown More Political in Recent Years

Key Takeaways

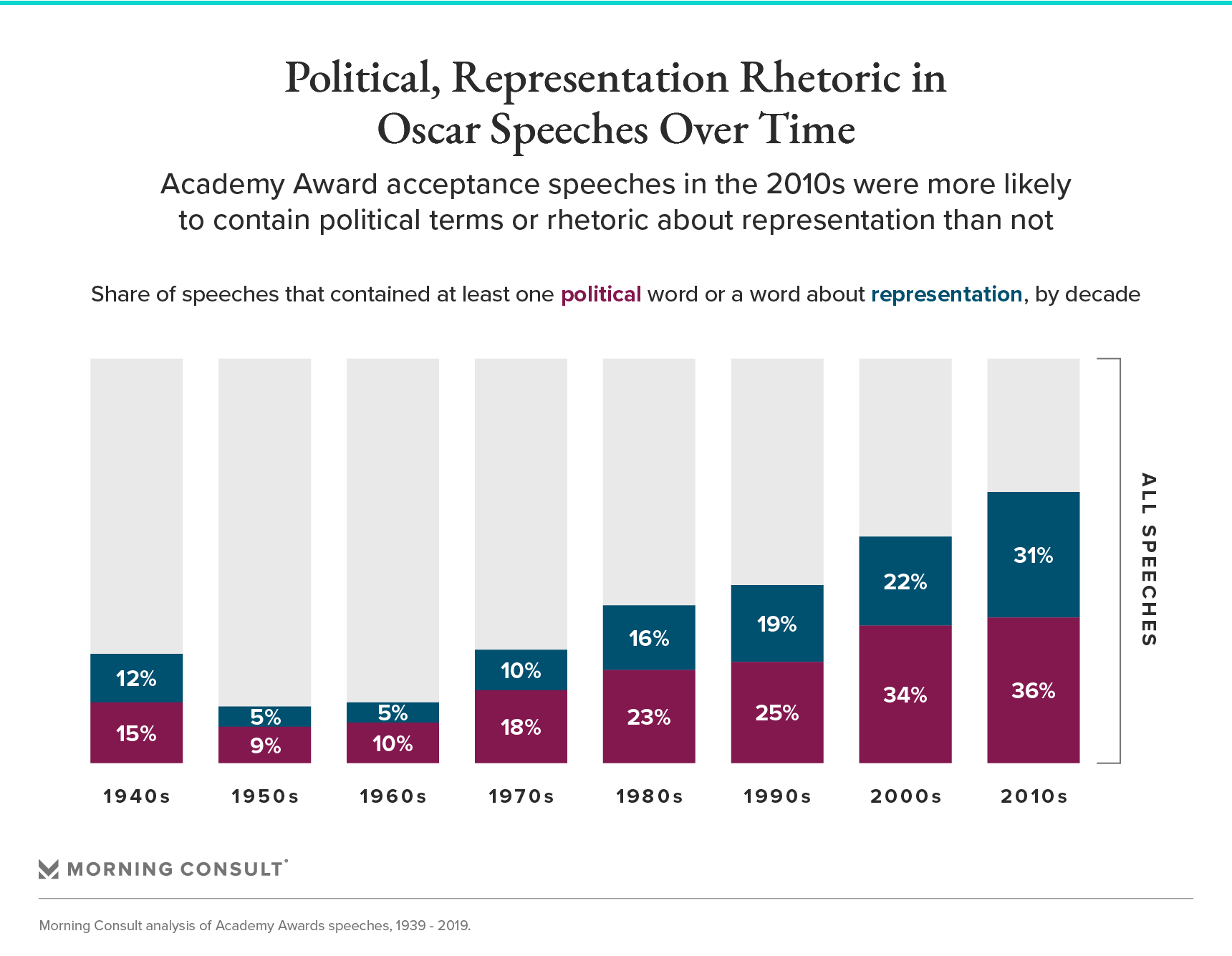

A Morning Consult analysis of more than 1,500 Oscar acceptance speeches dating back to 1939 found that while 22% of speeches overall contained one or more political words, 36% of speeches in the 2010s included political rhetoric.

Patricia Arquette’s best supporting actress acceptance speech in 2015 was deemed the most political, while Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy’s speech at the 2016 ceremony for best documentary (short subject) was the most focused on representation.

The longest acceptance speech -- 1,138 words -- occurred when the best picture trophy was mistakenly awarded to “La La Land” instead of “Moonlight” during the 2017 ceremony.

It’s become a common complaint, especially amid awards season, that Hollywood has gotten “too political.” Polling has shown that most of the public wants celebrities to stay mum on politics during awards broadcasts, even as stars have embraced using an awards podium to call attention to political and social injustices.

Morning Consult set out to answer this question by analyzing the content that takes up the bulk Academy Awards: acceptance speeches.

“There's been a huge effort to paint Hollywood as political,” said Howard Bragman, a longtime Hollywood crisis counselor and observer, who admitted that the industry can be political. Outspoken stars, such as Jane Fonda and Susan Sarandon, contribute to the idea that Hollywood is a largely political industry, he said.

An analysis of more than 1,500 Academy Award acceptance speeches dating back to 1939 found that speeches have grown slightly more political in recent years. While just five of the speeches analyzed from the 1940s included political rhetoric, that figure totaled 83, or 36 percent, in the 2010s. Mentions of representation also increased from four speeches in the 1940s to 72 speeches, or 31 percent, in the 2010s.

However, even with the number of political speeches growing in recent years, the majority contained only a few political words. Overall, 78 percent of the speeches analyzed did not include any political rhetoric. Among those that did, 94 percent contained three or fewer political words. Of all of the speeches analyzed, just four contained more than five political words.

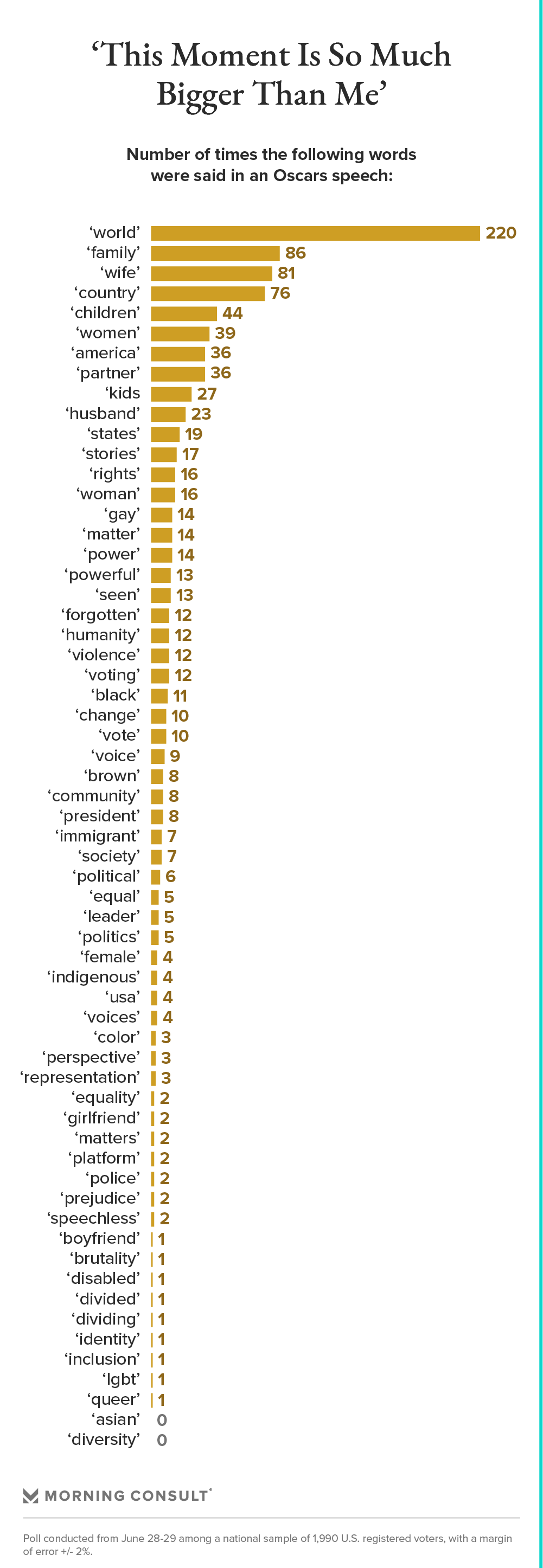

To determine the political saturation of speeches, 25 words — such as “immigrant,” “politics,” “vote” and “leader” — were deemed “political.” Speeches containing at least one of these words were marked as political, and those with more than one key word were marked accordingly.

Patricia Arquette’s best supporting actress acceptance speech for 2014’s “Boyhood” was the most political, according to the Morning Consult criteria. In her 176-word speech, in which she discussed wage equality and equal rights, there were 11 mentions of political words. (The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences database lists the year of the films being celebrated, not the year of the ceremony. So, while “Boyhood” was honored at 2015’s ceremony, it is listed as 2014, the year of its release.)

Stephen Galloway, former executive editor of The Hollywood Reporter who covered the Oscars for decades, added that because of the Oscar telecast’s lengthy run time -- which has topped three-and-a-half hours in recent years -- moments that catch the viewers’ attention are often the most remembered, which can create a false assumption that the Oscars are an overtly political event.

“Anything that happens that is different, controversial, exciting, unusual, will be discussed,” Galloway said. “The things that have happened tend to be people having some sort of political announcement.”

Common and John Legend’s speech for 2014’s best original song (“Glory” from “Selma”), which centered on civil rights and mass incarceration, included seven mentions of political rhetoric, per our analysis.

Some stars may shy away from mentioning politics to prevent alienating portions of their fan base. That’s the advice Richard Laermer, chief executive of RLM Public Relations in New York, would give to nominees.

“Be entertaining, be funny, find the light, cite the people that got you here, don't make it about God, because I think that offends people a lot,” Laermer said, “and stay away from politics because 50 percent of the country is not going to like what you have to say.”

A March 17-22 Morning Consult survey found that 45 percent of respondents would be less likely to watch an awards show if celebrities at the show expressed their political opinions, the most off-putting aspect polled.

While the analysis focused only on speeches and not other portions of the ceremony, such as the opening monologue or remarks made by presenters, there were no mentions of former President Donald Trump, a popular comedic target and lightning rod for the Hollywood set, in the speeches.

“Nobody wants to give him credence,” Bragman said of Trump. “It's kind of a rule: Don't give that person any attention.”

A lack of diversity across the biggest films and most celebrated stars has gained attention in recent years, particularly when the social movement #OscarsSoWhite launched online in 2015, the same year that every major acting category featured only white nominees. While representation can be interpreted as a political issue, because of the increased conversation around the topic of Hollywood diversity and representation in recent years, Morning Consult decided to look specifically at how much representation was being discussed in speeches.

“When #OscarsSoWhite hit, it had an enormous effect on the Academy,” said Galloway, who also serves as the dean of the Chapman University film school. “The academy changed its membership and almost doubled.”

In 2020, the Academy invited 819 individuals -- 45 percent of whom were women and 36 percent of whom belonged to underrepresented ethnic and racial communities -- to join its ranks. The organization also announced it surpassed its goal of doubling its female and underrepresented members by 2020. Last year, the Academy issued a set of guidelines to go into effect with the 2022 Oscars, calling for films to meet criteria for representation on-screen and behind the camera.

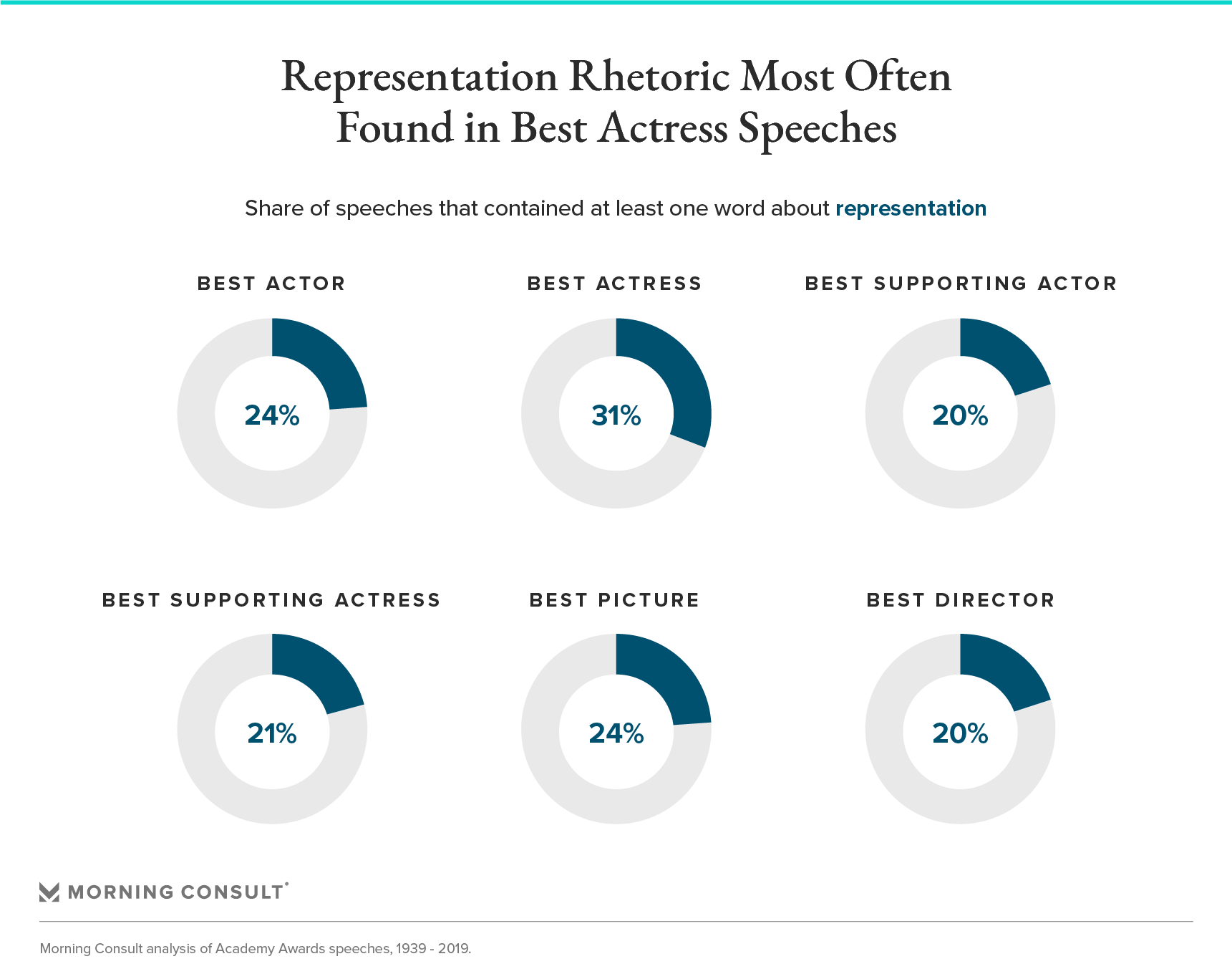

However, even with this increased focus on representation, an even smaller share of speeches (16 percent) mention this topic, according to the Morning Consult analysis, which focused on 24 words, including “community,” “identity” and “stories.” Speeches containing at least one of these words were marked as representation, and those with more than one key word were marked accordingly.

Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy’s speech for 2015’s best documentary (short subject) featured the most mentions of words related to representation. In her speech, the filmmaker discussed women and honor killings.

While Joaquin Phoenix’s “Joker” acceptance speech last year was one of the most focused on representation, it was equally focused on politics. His 353-word address had relatively few expressions of gratitude, and instead focused heavily on equal rights and environmentalism, including a memorable mention of the inhumane treatment of cows.

Frances McDormand, a two-time best actress winner whose “Nomadland” performance is nominated in this year’s category, used both of her acceptance speeches to shine a light on Hollywood’s shortcomings with representation: In 1997, she called on “writers and directors to keep these really interesting female roles coming,” and in 2018, she highlighted the night’s female nominees and brought attention to the use of inclusion riders, or contractual stipulations actors can have that require diversity among casts and crews.

Experts interviewed for this piece said that the idea of the Oscars as a political event can likely be tied to Marlon Brando’s decision to send Sacheen Littlefeather to decline his best actor award at the 1973 ceremony for “The Godfather.” Littlefeather’s appearance, which Brando coordinated as a rebuke of Hollywood’s depictions of Native Americans, resulted in the Academy prohibiting proxy acceptance of awards in future years.

The evolution of the Oscar ceremony itself has impacted the content and length of speeches. Early on, it was a brief ceremony attended by only a few hundred people, making headline-worthy moments hard to come by.

“You could stand up in front of an audience and throw out ‘inclusion rider’ and it wouldn't make an impact,” Galloway said. He added that societal changes have normalized making a statement about politics or society with an acceptance speech.

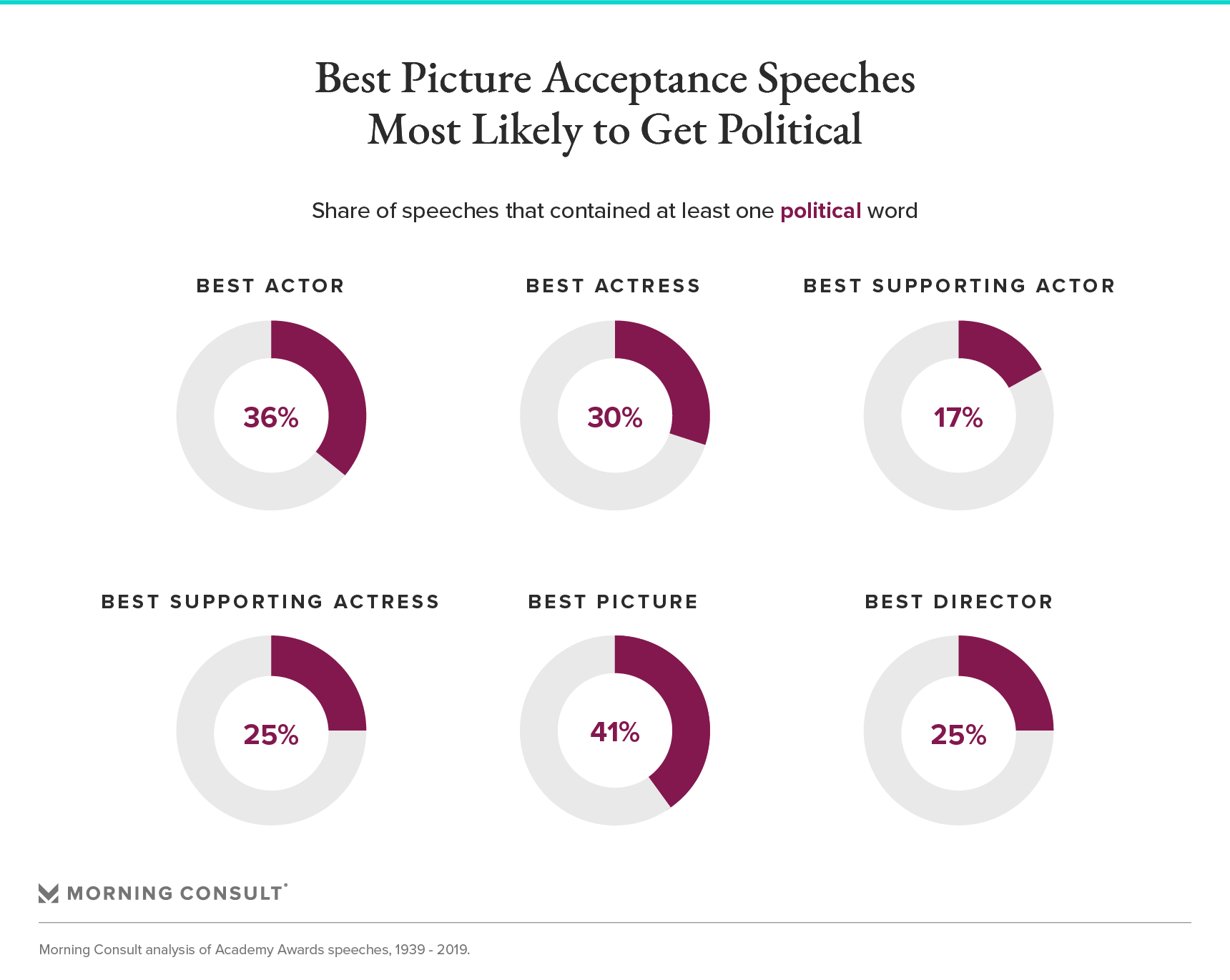

Among the above-the-line categories, winners for best picture and best actor were most likely to get political, while best actress winners were most likely to discuss representation.

Black Lives Matter, Time’s Up and #MeToo have contributed to an increased focus on political and social movements in the mid-to-late 2010s, with the latter two movements emerging from the entertainment industry alongside the allegations of sexual assault and misconduct against Harvey Weinstein and other powerful figures.

“A lot of people in the entertainment industry feel like they have to stand for something,” said Laermer, adding that the industry connection to these movements creates additional motivation for stars to speak up about important issues.

A September Morning Consult survey found that 54 percent of all adults said celebrities should share their views on political and social issues. Nine percent said stars should use events such as award shows to speak out.

“To make a political speech and a socially conscious speech, those are two different things,” Galloway said. “The socially conscious speech is much less risky than an overtly political speech.”

Speeches have also become longer over time. In the 1950s, the average length of an Oscars acceptance speech was 35 words. That climbed to 48 words in the 1960s and 104 words in the 1970s. The average length of a speech in the 2010s was 190 words.

The last decade also housed the ceremony’s two longest speeches to date. The speech for 2016’s best picture was the infamous mix-up in which “La La Land” was incorrectly named over the actual winner, “Moonlight,” is the longest at 1,138 words. Grant Heslov and Ben Affleck’s speech accepting the 2012 best picture trophy for “Argo” is the second-longest at 633 words.

As Halle Berry acknowledged in 2002 ("This moment is so much bigger than me"), award winners have increasingly used their speeches to thank family members and those who have helped them along the way.

Mentions of family members, including partners, spouses and children, have become more common than political or representation rhetoric, with 35 percent of the speeches analyzed including mentions of these people. “Family” was the second most popular word analyzed over the 80 years of speeches, clocking in at 86 mentions, followed closely by “wife,” which was said 81 times. “World” was mentioned most frequently, nearly three times the frequency of “family” and “wife.”

With the pandemic calling attention to inequities and injustices around the world, there’s a chance that the speeches heard Sunday could embrace political and social issues more than usual. But industry insiders added that Oscars are no more political than any other event — they’re just a sign of the times.

Samantha Elbouez, Laura Maxwell and Erin Morris contributed to this story.

Sarah Shevenock previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering the business of entertainment.