Racial Divides Persist on Compensation for Student-Athletes

Key Takeaways

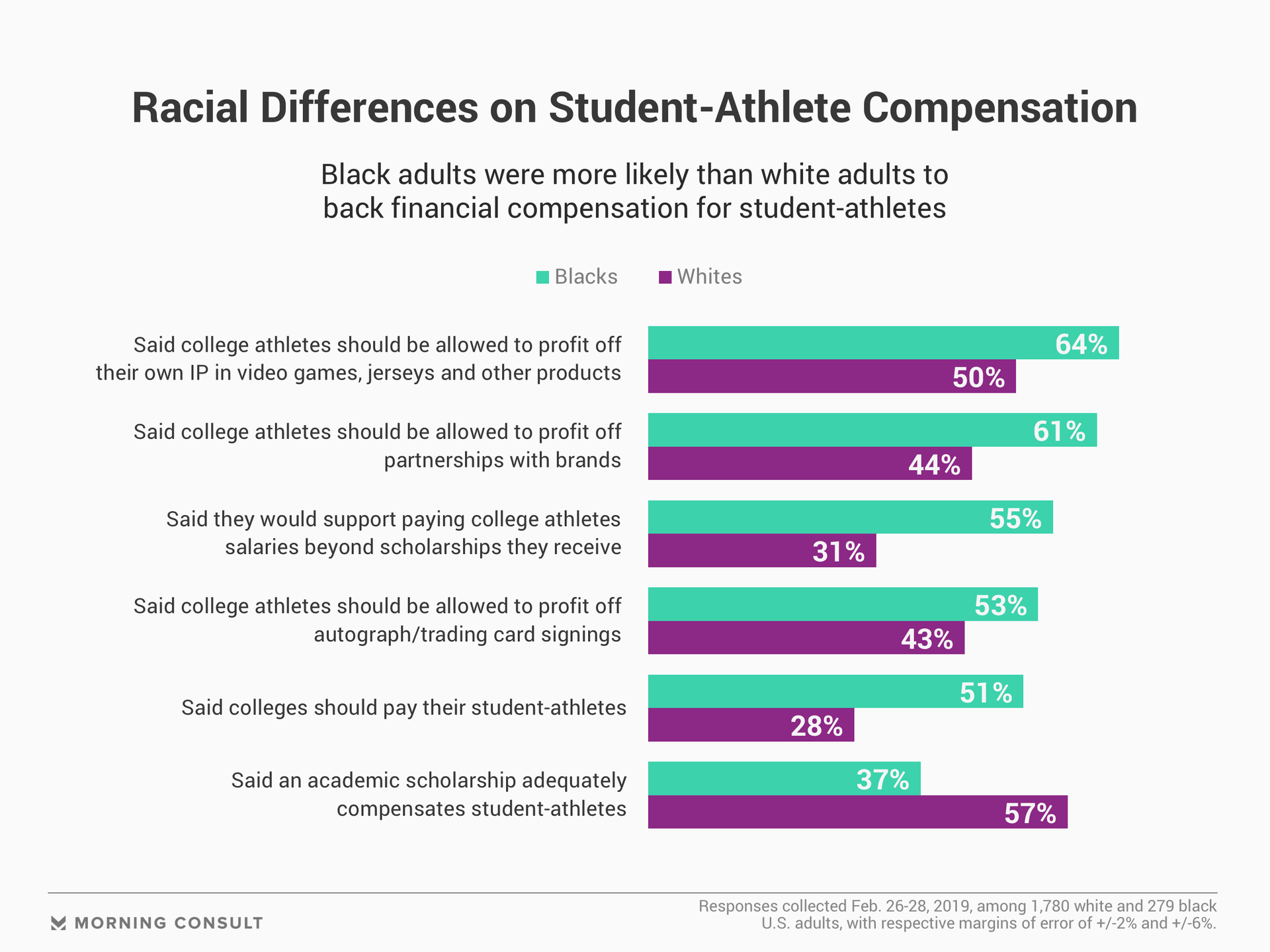

55% of black adults support paying salaries to college athletes, compared with 31% of white adults.

Black adults were also more likely to support amateurs partnering with brands and profiting off their name or likeness.

Black adults were more than twice as likely as whites to prefer pro sports to college sports.

The NCAA has spent much of the past decade fighting litigation from current and former student-athletes seeking compensation for their contributions in revenue-generating sports such as football and basketball, with one sociologist calling the uprising “the civil rights movement of our times.”

And as the NCAA Tournament, the governing body’s flagship event, tips off in earnest Thursday, a recent Morning Consult survey reveals a racial divide among the public when it comes to these collegiate amateurs -- many of whom are black -- and their rights to remuneration, which has been consistently rebuked by the NCAA.

In 2018, 56 percent of Division I men’s college basketball players and 48 percent of football student-athletes were black, according to an NCAA database.

The Feb. 26-28 survey of 2,201 U.S. adults found that 55 percent of black respondents supported paying student athletes a salary, compared with 31 percent of white respondents. And while 57 percent of white Americans said an academic scholarship is adequate compensation for student athletes, black Americans were almost split, with 37 percent saying yes and 39 percent disagreeing.

The survey polled 1,780 white U.S. adults and 279 black U.S. adults, with each subgroup having respective margins of error of plus or minus 2 and 6 percentage points.

Black Americans were also more likely than white Americans to support college athletes profiting off their name or likeness by partnering with brands, signing autographs or having intellectual property ownership in video games, jerseys or other products.

Professor Joe Feagin of Texas A&M University -- whose research has centered around racial and ethnic relations -- placed the discrepancy in sentiment into the context of the country’s history of slavery. For nearly all of the 20 generations of the country’s founding, Feagin explained, blacks didn’t have legal equality and opportunity, as the Jim Crow system of racial segregation was only struck down in the late 1960s.

“Any of these questions where it opens up more opportunities are going to be valued more heavily by blacks,” said Feagin, who added that the historical absence of the “cross-generational transmission of resources and wealth” for blacks is, in large part, the underlying explanation for why those surveyed sided more heavily with student-athletes.

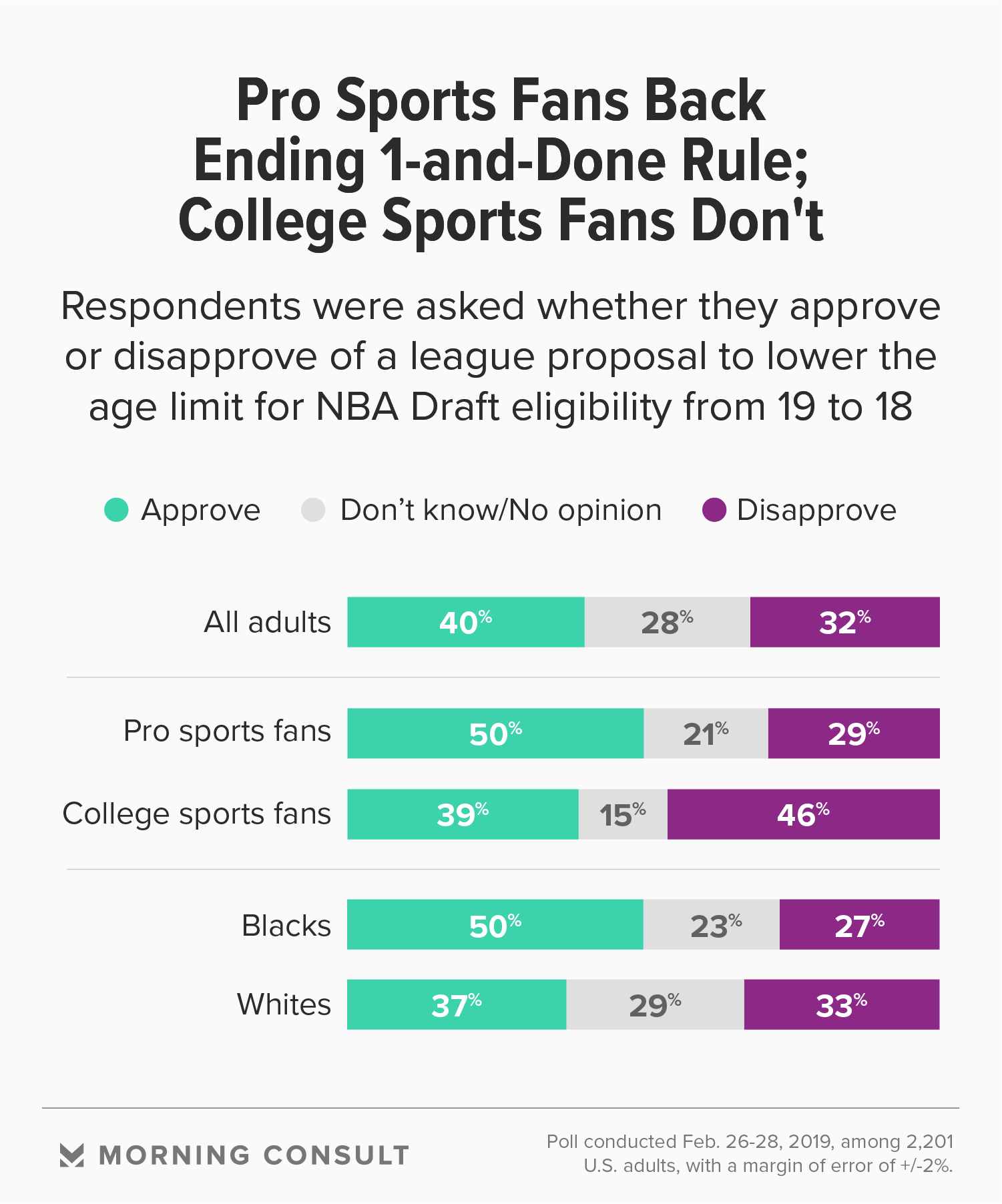

Those financial opportunities Feagin alluded to include the NBA’s proposal to lower its draft eligibility age from 19 to 18 and thus, eliminating its 2005 “one-and-done” rule, which helped force the country’s top prep basketball stars to spend at least one year in college.

“When those families have talented athletes coming up in elementary and secondary schools, they are quite aware that there’s an opportunity here to generate resources for their families that is very difficult to come by in a systematically racist society,” Feagin said. “Over those 20 generations, we whites have been unjustly enriched, and over those 20 generations, black families have been unjustly impoverished.”

Racial differences appeared again concerning the approval of the NBA’s plan to eliminate the one-and-done rule: Fifty percent of black respondents supported the proposal, compared with 37 percent of white respondents.

Support for ending one-and-done along racial lines was mirrored among those who preferred pro sports to college sports. That’s, in part, because whites were more likely than blacks to be college sports fans. Although the lion’s share (44 percent) of whites surveyed said they prefer pro sports to college sports (26 percent), blacks favored pro sports over college athletics by a 40-point margin, 56 percent to 16 percent.

College athletics is big business in the 21st century. Hundreds of millions of dollars are funneled into state-of-the-art facilities, and many coaches are on seven-figure salaries. The NCAA and CBS/Turner signed an eight-year, $8.8 billion extension in 2016 that’ll see the NCAA Tournament broadcast through 2032 on both networks. A minimum of 25 million-plus viewers have tuned into the first five College Football Playoff championships since the 2014-15 season. And according to Forbes, the top 20 most valuable college basketball teams combined generated over half a billion dollars in revenue annually from 2014-15 to 2016-17, with more than a third stemming from media contracts.

With that kind of money flowing, said ESPN college basketball analyst Jay Bilas, revenue-generating players should be treated as professionals, and concerns over amateurism -- the supposed purity of players playing for something other than money -- ignore reality.

In an interview, Bilas said the NCAA and its member institutions should stop “trying to hide from the reality that they’re running professional sports” and allow those athletes to receive compensation in some form or other.

While the NCAA and the current college sports system still appear to have problems for some, including Bilas, only 8 percent of all adults surveyed said those issues were insurmountable.

“We still want to have a regulating body in some ways that is trying to do the right thing, even if they don’t believe the NCAA is currently making the best decisions right now,” said professor Andy Billings, director of the Alabama Program in Sports Communication. “It’s that desire to embrace that institution that they can count on. The fear of the unknown, the fear of -- OK, what happens if we get rid of this institution? -- is still very real.”

The NCAA did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Mark J. Burns previously worked at Morning Consult as a sports analyst.

Related content

As Yoon Visits White House, Public Opinion Headwinds Are Swirling at Home

The Salience of Abortion Rights, Which Helped Democrats Mightily in 2022, Has Started to Fade