Energy

Report: $2.2 Billion Needed to Meet U.S. Electric Car Charging Demand Through 2025

As discussions unfold over how and to what extent the federal government should help electrify the transportation sector, an international nonprofit estimates that it will cost the United States a total of more than $2.2 billion from now through 2025 to make the investments needed across the most populous U.S. areas to meet increased electric vehicle demand.

The International Council on Clean Transportation, in a report released Tuesday morning, said $1.3 billion would be needed to make the necessary additions to home charging for electric vehicles and $940 million for workplace and public charging for the 100 U.S. metro areas with the highest populations.

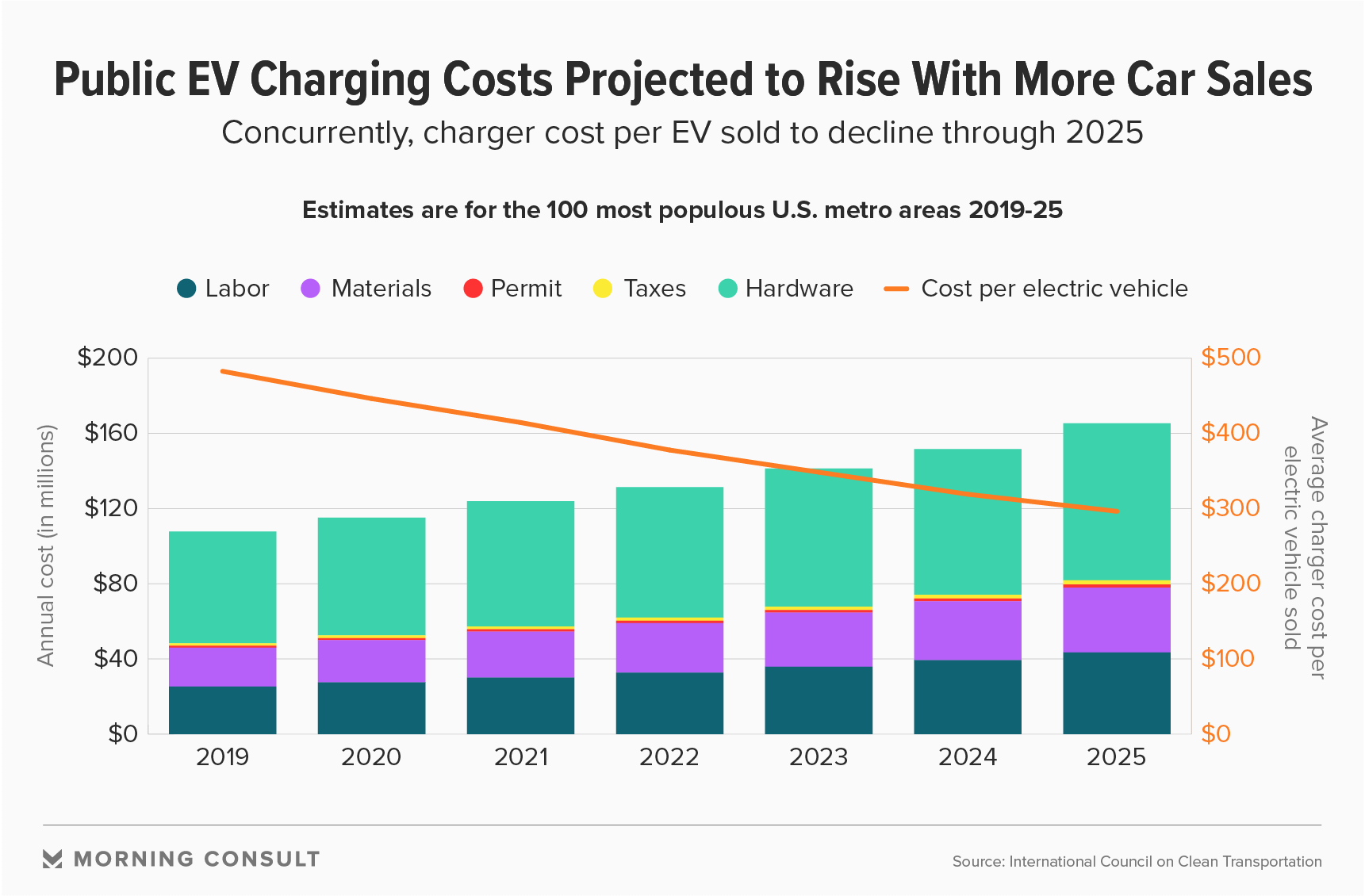

Those 100 metro areas represent 88 percent of new electric vehicles sold and 75 percent of the U.S. vehicle market as a whole. Estimates include the costs of hardware, permits, taxes, materials and labor but do not include some potential external costs, such as putting in lighting or security cameras.

The study builds on the council’s earlier report, released in January, that estimates a need for 82,000 more charging stations at workplaces, 103,000 public stations of 208-volt to 240-volt (Level 2) chargers and 10,000 direct current fast charging stations by 2025 to meet anticipated electric vehicle growth in those same metropolitan areas — or 4.3 times the number of public charge points than existed at the close of 2017.

The extent of the gap and its cost are critical considerations, given that a concern over a dearth of sufficient charging infrastructure is still the top reason prospective electric vehicle buyers would be less likely to opt for such a car, according to Morning Consult polling from March.

The council’s latest report examines end-use data of how consumers actually charge their electric vehicles, said author Michael Nicholas, a senior researcher in the council’s electric vehicle program.

While Nicholas projects the total cost of public and workplace charger infrastructure to increase each year from 2019 to 2025 as electric vehicle sales increase, the average charger cost for each new electric vehicle sale is estimated to decline from $480 in 2019 to $300 by 2025, the report states.

That’s in part because even in metro areas with very few electric vehicles, chargers are still needed in many different locations, even though they may only be used for a short period. But critically, Nicholas finds that increasing the number of electric vehicles in the area does not require increasing the number of available chargers at the same rate, so fewer chargers are needed per car.

Installation costs also decline with the number of chargers placed at a given site, which the report finds increases with greater electric vehicle penetration. The report also assumes a 3 percent annual drop in charger hardware costs.

Nicholas cautions that those averages are of all charger costs per electric vehicle and include those vehicles whose owners do not use public infrastructure.

The report does not include costs for installations in smaller cities or across key highways between cities, and the study works with several assumptions, such as that Level 1 (regular outlets) and Level 2 chargers produce power at the high end of their typical power range.

Beyond the time period covered in the study, it is possible that costs could increase as electrification expands into the future. At this stage, Nicholas said, many installers are going for “the low-hanging fruit,” placing infrastructure at the easier, cheaper places to install, such as parking spots near a transformer. So he said he expects the decline in average charger cost per vehicle will eventually bottom out and possibly rise.

The data arrives as policymakers grapple with how or where to fund public charging infrastructure and comes soon after the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee’s release and approval of a surface transportation authorization bill whose climate change section would create a federal grant program for electric vehicle charging and other fueling infrastructure grants worth $1 billion from fiscal 2021-25.

Chet Thompson, president and chief executive of the American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers trade group, said through a spokesman via email Monday that improving U.S. infrastructure should be a top priority. But rather than use tax dollars to subsidize the infrastructure for electric vehicles and the sale of cars, “which are enjoyed primarily by wealthy Americans living on the coasts, we should focus on bolstering U.S. infrastructure in ways that will equally lift the quality of life for all Americans,” he said.

Nicholas said in less-active electric vehicle markets, “there’s an opportunity to provide this geographic coverage.” Even for chargers that get installed in odd places, it has become clear in California, for example, that eventually those chargers still get car traffic.

“There's no bad spot for a charger, eventually, in a growing market,” Nicholas said.

Jacqueline Toth previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering energy and climate change.