Catfishing Cases and the Financial Losses That Come With Them Are Rising. The Public Wants Social Media Companies, Lawmakers to Crack Down on the Issue

Key Takeaways

The FBI said more than 23,000 people reported being catfishing victims in 2020 and sent scammers more than $600 million.

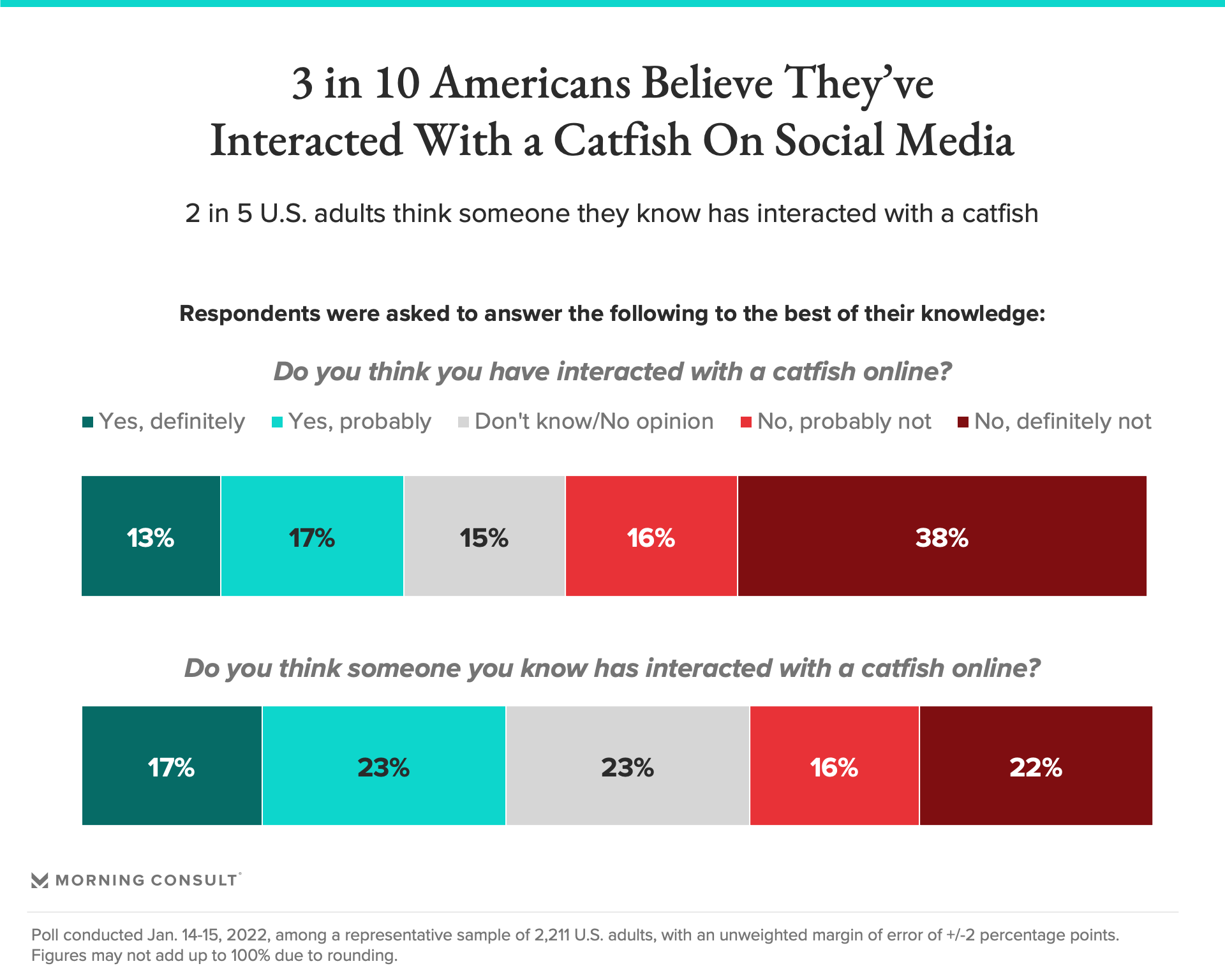

While victim reports are on the rise nationally, Morning Consult polling found that the majority of the public said they have not interacted with a catfish.

Oklahoma is the only U.S. state to make catfishing punishable through a civil action, and some experts have said social media should be heavily regulated to stop the trend.

Nearly a decade after a movie and MTV show began spotlighting cases of catfishing to a mostly unaware public, a debate over the practice of creating fake personas online is playing out between law enforcement in Los Angeles and the world’s largest social media company.

Following a September report from the Brennan Center for Justice that found Los Angeles Police Department officers extensively surveil social media with little oversight or internal monitoring and build fake profiles of people, Meta Platforms Inc.’s vice president and deputy general counsel for civil rights wrote in a letter to the LAPD’s chief that the practice violates the company’s terms of service and should be halted immediately.

While it does not constitute catfishing in the truest sense of the word, it contains elements of the practice in a bid for the LAPD to advance its criminal surveillance efforts.

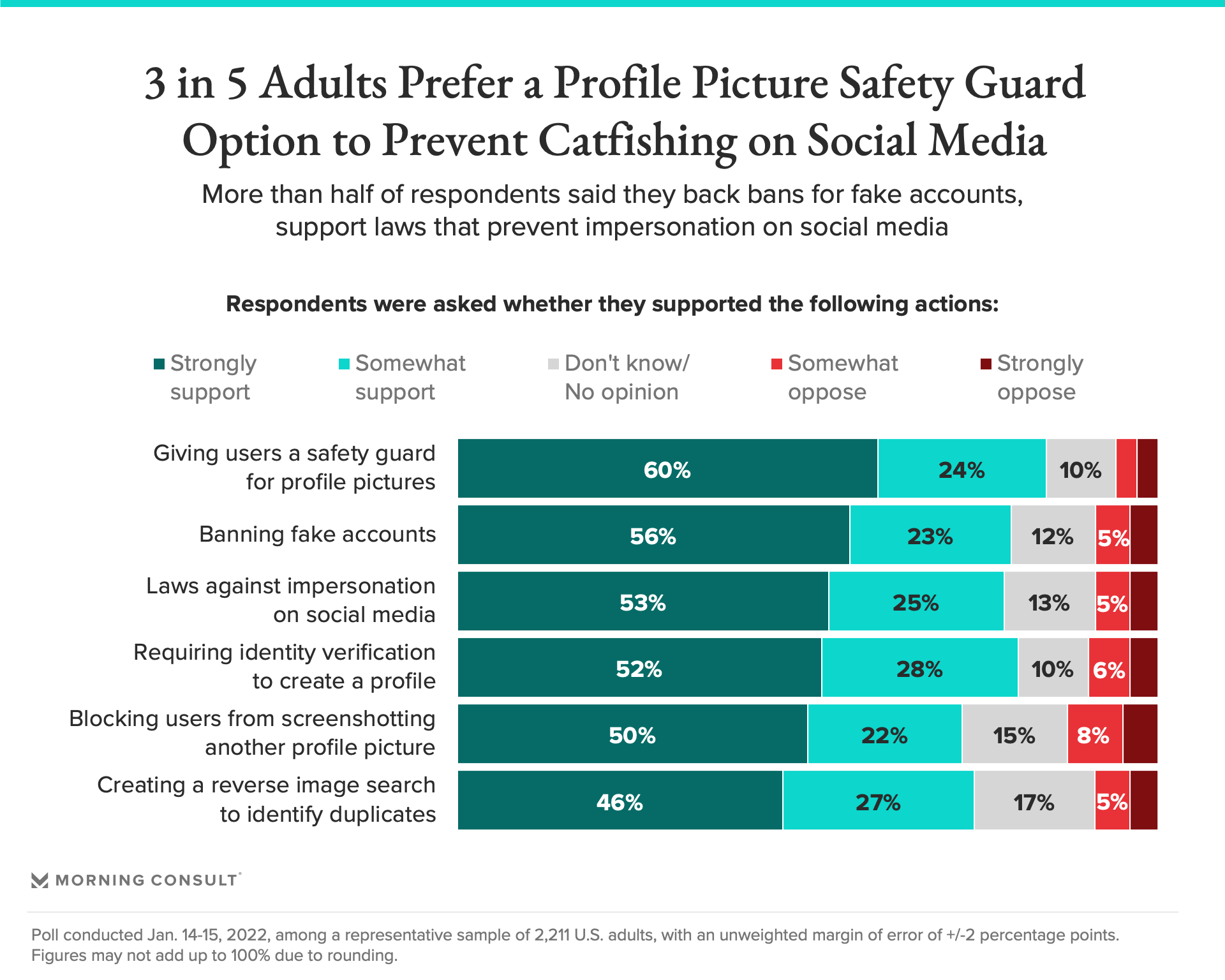

Meta’s objection to the use of fake profiles and catfishing, where users are tricked by fake accounts into online relationships and sometimes scammed out of money, is a stance that the public seems inclined to support: A new Morning Consult poll found that nearly 4 in 5 U.S. adults back social media companies to ban fake accounts, while a nearly identical share is in favor of regulators creating laws to prevent impersonation or fake accounts on social media.

Meta and LAPD spokespeople did not respond to requests for comment on the letter’s contents or any potential repercussions. But anti-catfishing advocates and experts on social media trends say the spat highlights the need for catfishing to be made illegal, a move that would finally address the myriad safety and financial concerns wrought by the practice.

Rising instances of catfishing – and soaring financial losses

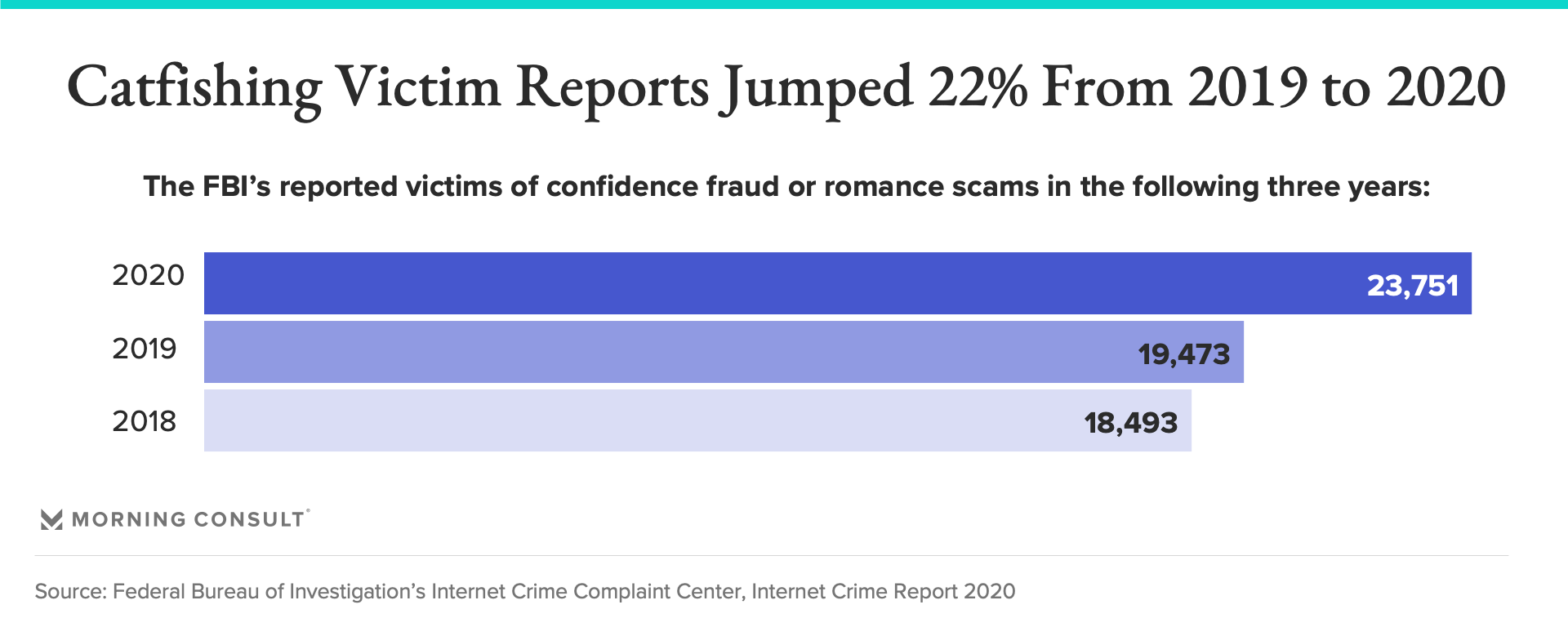

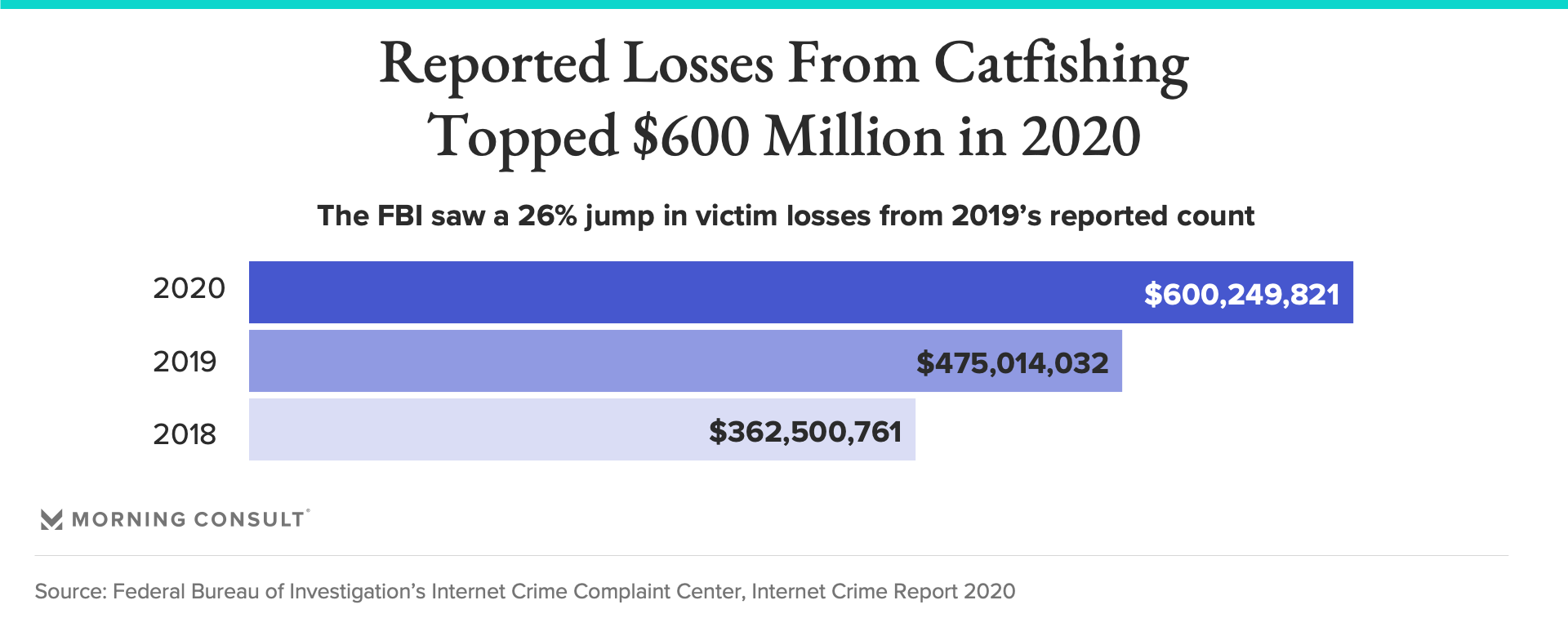

Statistics collected by the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Internet Crime Complaint Center show the staggering financial effects of catfishing on victims in the United States.

In its 2020 Internet Crime Report, IC3 reported 23,751 victims of “confidence fraud” and “romance scams” — as it defines catfishing — in 2020, a 22 percent increase from 2019. Victims’ reported financial losses topped more than $600 million in 2020, a 26 percent year-over-year rise.

“Confidence fraud, or romance scams, can happen to anyone at any time,” a spokesperson for the FBI’s Washington Field Office said in an email. “The criminals who carry out romance scams are experts at what they do. Individuals who are looking for love and companionship are the target victims of this online fraud. The FBI cautions everyone who may be romantically involved with a person online to proceed carefully and stay alert to warning signs.”

Anna Rowe, a U.K. resident who started a victims support network after she was deceived by a married man who used a fake identity to solicit sexual relationships from women online, said any new legislation should combat the intent behind catfishing – for example, if it is done to solicit money or a sexual relationship or exploit the victim in any way.

In the United States currently, prosecutions are only likely possible if money changes hands, like in the Northern District of Texas, where 11 romance scammers were indicted for money laundering and wire fraud last year. Spokespeople with the Federal Trade Commission, which also has jurisdiction over the financial aspect of catfishing, did not respond to requests for comment.

Lawmakers in the United Kingdom, meanwhile, are currently debating legislation that would regulate online content and the harm users can suffer. Rowe said a new law should include anti-catfishing provisions; the U.K. Parliament previously debated catfishing legislation in 2017.

“There are obviously certain people who need the protection of anonymous profiles, like domestic abuse victims, certain professions, like the police who don't want to have their real name,” Rowe said. “For me, the law needs to have the caveat of intent behind it. But what is good about online evidence is that it's there in black and white, so if that fake profile is used for something criminal, then it shows the intent.”

The public views catfishing as a problem, though personal interactions with fake accounts are limited

Just over half of U.S. adults said they have not been affected by catfishing. Meanwhile, 30 percent of respondents in the Morning Consult survey said they believed they had interacted with a catfish online, while 40 percent said they believed someone they know has done so. Just 16 percent said they believe they or someone they know has sent money to a catfish.

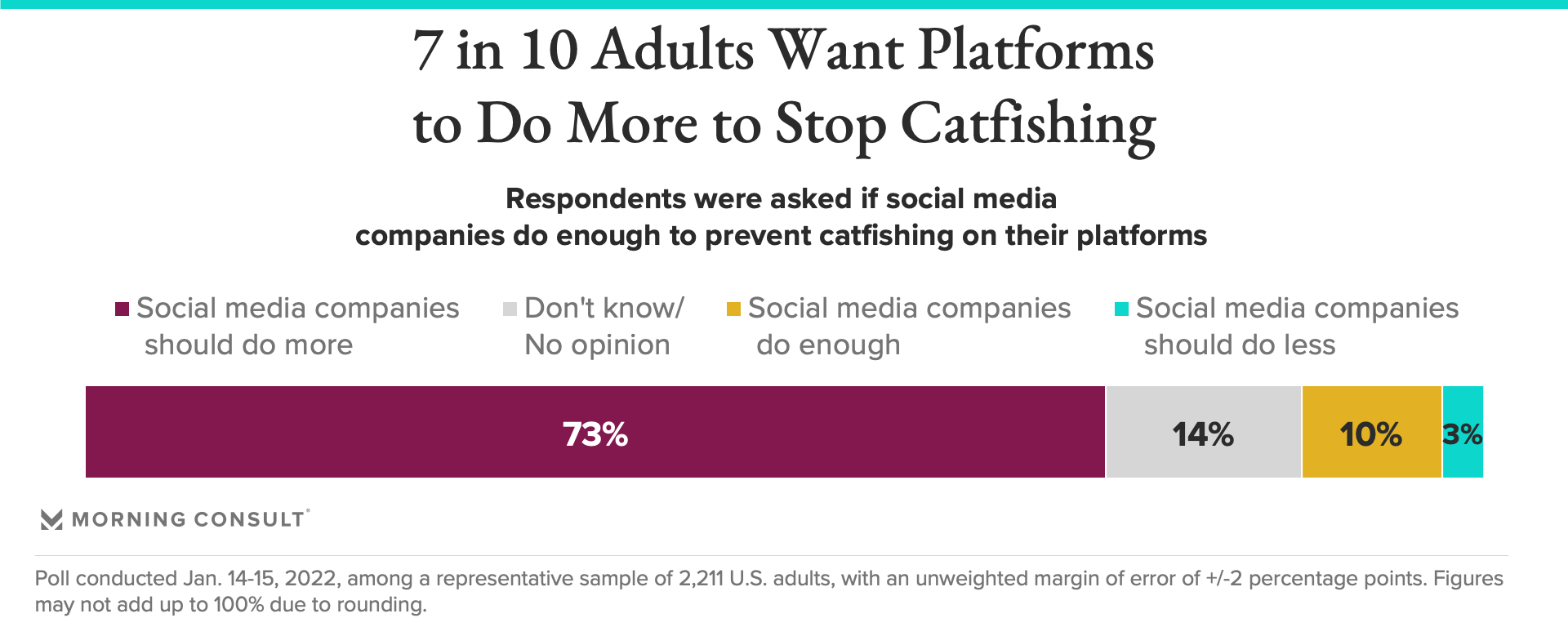

But the public believes catfishing is a problem. Seventy-three percent said social media companies should do more to identify and remove potential catfish from their platforms, compared to just 10 percent who said the platforms are doing enough. And while social media companies argue that they have policies in place to combat catfishing, others are skeptical.

“I don't want the opinion of social media companies about how well they're doing,” said Christie Nordhielm, an associate teaching professor of marketing at Georgetown University’s McDonough School of Business. “I want the opinion of a neutral third party. The fox can't run the henhouse, and that's what's happening right now.”

For its part, Meta says it already takes action to protect “Account Integrity and Authentic Identity,” including by banning users for impersonating others and for maintaining multiple accounts as a single user.

Nevertheless, there’s an appetite among the public for social media platforms to do more to combat catfishing.

Regulations targeting catfishing are scarce

Oklahoma passed a law in 2016 to make catfishing punishable through a civil action, and so far, is the only state to do so. Other states have banned online impersonation generally. The Oklahoma legislation made anyone found to have created a false identity on social media “for the purpose of harming, intimidating, threatening or defrauding” liable for the crime of online impersonation and liable for any damages sustained by a victim.

The law contains a carve-out for law enforcement agencies, so long as they are “acting within the scope of their employment investigating Internet crimes,” an argument that the LAPD could potentially make with Meta about the use of its platform for its surveillance efforts. The law also protects the social media companies themselves from liability.

Even with the law in place, the FBI’s data shows Oklahoma reported 212 victims of confidence fraud and romance scams in 2020, with financial losses totaling about $4.5 million. A spokesperson for the Oklahoma Attorney General’s office declined to comment on the figures, but noted that the state’s catfishing law is not something the state enforces, but instead “creates a civil cause of action that the victim must pursue on his/her own.”

The only other state to have appeared to have attempted a similar ban is Wisconsin, where a 2017 bill passed the state Senate’s Committee on Judiciary and Public Safety but did not receive a floor vote, and a 2019 proposal died in committee.

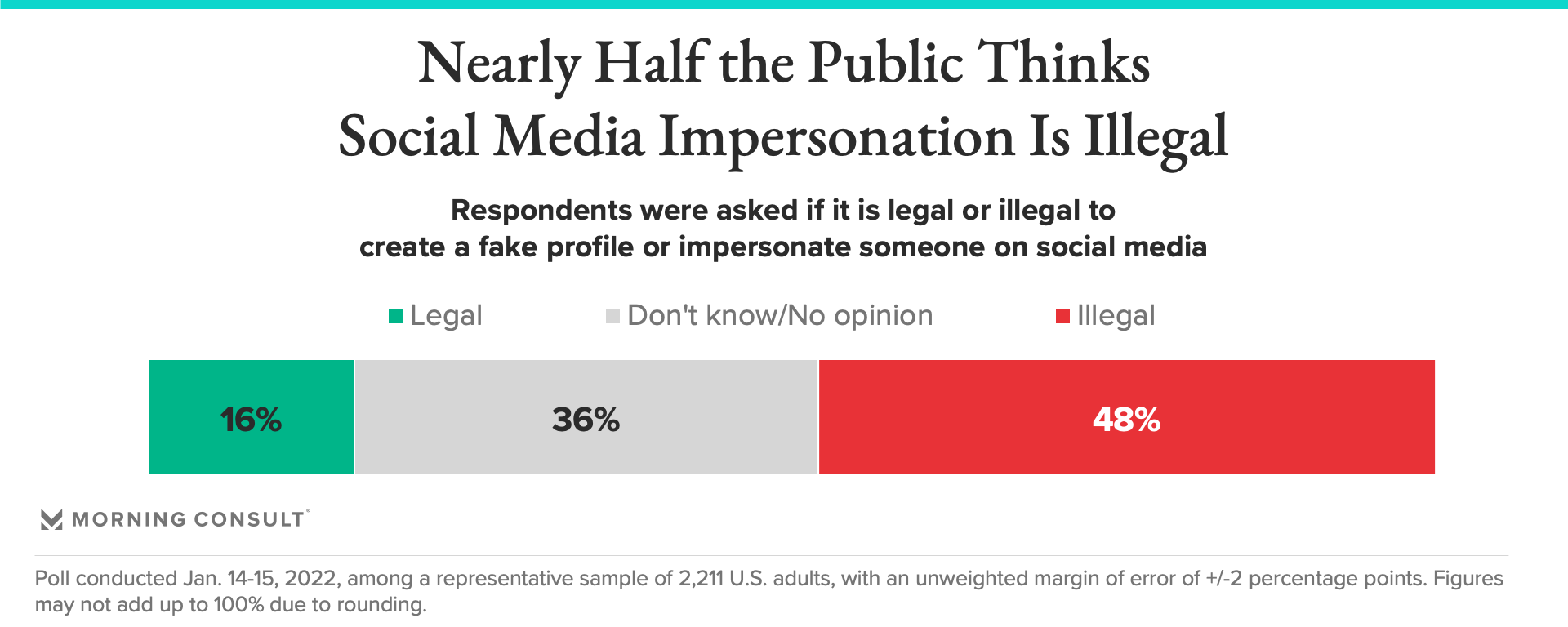

Nearly half the public said they believed it is illegal to create a fake persona or impersonate someone on social media, compared to 16 percent who said they believed it is legal.

Nordhielm said regulation of social media could echo the Communications Act of 1934, which first created the Federal Communications Commission and gave it oversight powers to ensure that television and other broadcast media served a public good.

Given how the social media landscape has evolved, and even after provisions of that act were amended or repealed by the Telecommunications Act of 1996, Nordhielm said there’s no “reason why the broadcast community should be under a different set of regulations than the internet platform community, which provides pretty much indistinguishable content and services.”

Educating users about the dangers of social media could be an effective way to curb catfishing, she added. A Florida bill that would require social media literacy to be taught in the state’s public schools received strong support from registered voters in a Morning Consult/Politico poll last year, and Nordhielm said that better education combined with stronger efforts by the platforms themselves represents the best way to curb many bad behaviors on social media.

“That should just be a part of the educational process for global citizens,” she said. And “certainly citizens of the United States.”

Chris Teale previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering technology.