Energy

Ahead of 2020, Democrats See Climate 'Crisis' Where Republicans See 'Problem'

Key Takeaways

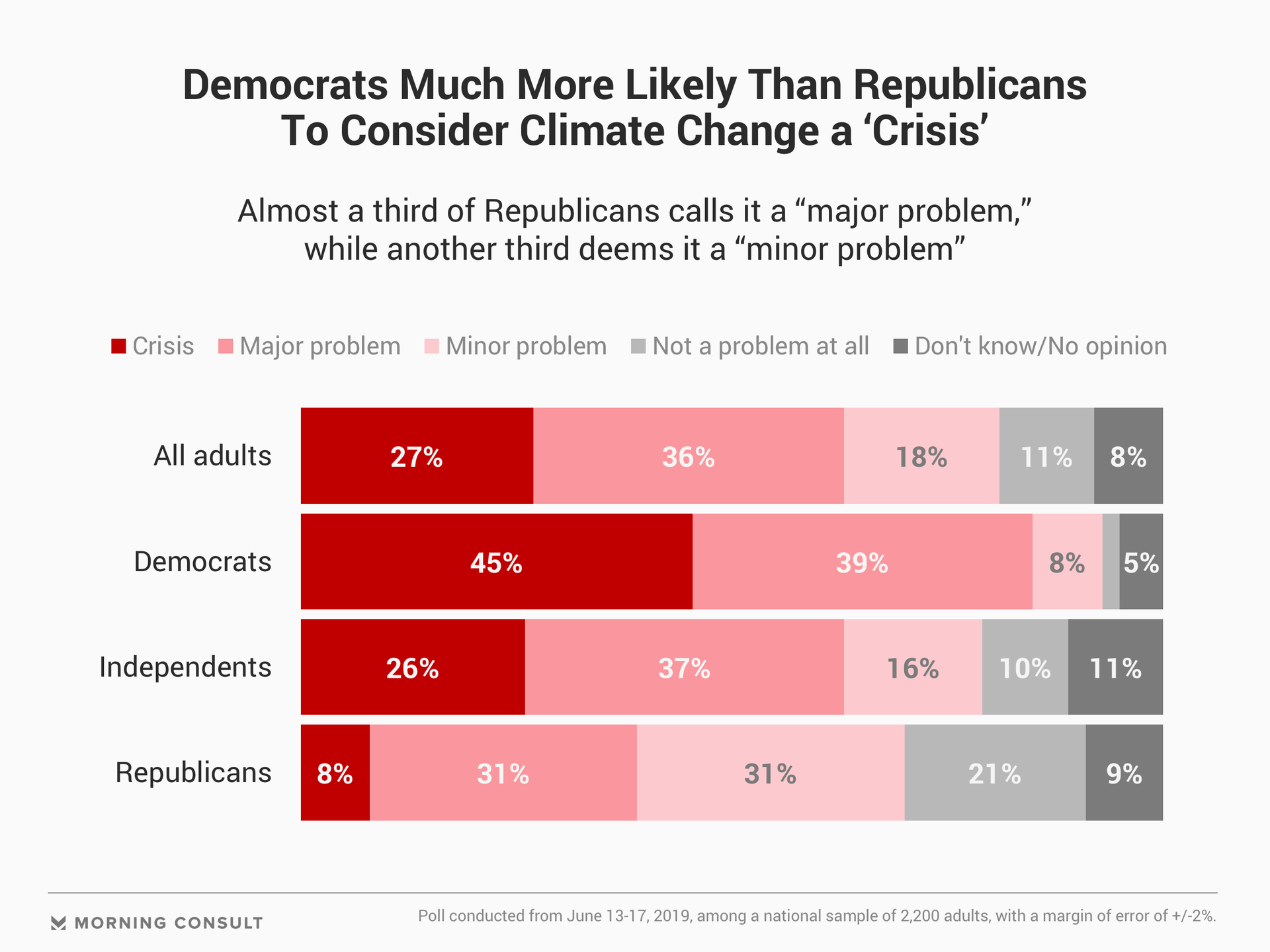

45% of Democrats, 26% of independents and 8% of Republicans deemed climate change a crisis.

62% of adults said climate change makes natural disasters more frequent, and 60% said it makes storms more powerful.

Tropical Storm Barry has developed in the Gulf of Mexico with the possibility of upgrading to a hurricane, and wildfires have impacted 855,000 acres in Alaska alone this year so far. Amid these events, there is still an intense partisan divide over concern about climate change and its role in extreme weather, according to a recent poll.

A Morning Consult survey of 2,200 U.S. adults conducted June 13-17 found that 45 percent of Democrats said they consider climate change a crisis, compared with 26 percent of independents and 8 percent of Republicans. The poll, which has a margin of error of 2 percentage points, underscores the possibility that an extreme weather period between now and November of next year could have some impact on the 2020 elections. But environmental researchers say it’s unclear whether such natural disasters are likely to drive voter turnout or demonstrably affect outcomes.

After Hurricane Harvey and during Hurricane Irma, a Morning Consult poll in September 2017 found an uptick of 7 points in Republican voter concern over climate change and its impact on the environment to 57 percent, with a 3-point margin of error for the party. But those numbers subsequently declined, and no comparable increase was seen during the difficult 2018 Western wildfire season. In February, 41 percent of GOP voters said they were concerned about climate change’s impact on the U.S. environment, compared to 88 percent of Democrats.

Close to 2 in 3 adults said climate change is making natural disasters more frequent and stronger, similar to registered voters polled in October 2018, after Hurricane Florence had passed over North Carolina and as Hurricane Michael was concluding in the South.

Those numbers were both increased from voter polling in September 2017, when 52 percent said that climate change makes natural disasters more frequent and more powerful. But the spike is attributable to a rise in Democratic belief that climate change increases the number and strength of extreme weather: While 67 percent of Democrats said that climate change makes storms more frequent from the September 2017 poll of voters, that number increased to 83 percent in October 2018. Meanwhile, Republican belief in climate change’s impact on the frequency of storms has remained nearly constant, at 40 percent among voters in 2017 and 42 percent in 2018.

Sixty-two percent of adults in June said climate change makes extreme weather events more frequent, and 60 percent said stronger, compared to 63 and 61 percent, respectively, of voters from October of last year.

And the party divide remains, with 80 percent of Democrats, 61 percent of independents and 43 percent of Republicans believing that climate change makes natural disasters occur more often.

Whether a particularly active stretch of hurricanes or fires in the United States would have an impact on next year’s elections remains up for debate.

The 2020 elections are unprecedented in that climate issues are getting more attention than in the past — but it is mostly salient among activists and primary voters, said Parrish Bergquist, a post-doctoral researcher at the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. “We still don’t know how important it will be in the general election,” she said.

While research has shown that extreme weather events can have a short-lived impact on climate change opinions, “one thing we don't know yet is how these effects might accumulate over time and how they might change in magnitude as these events get more and more frequent,” Bergquist said.

It also depends in part on how public figures and the media talk about the storms, which can affect the public's opinions on climate change, Bergquist said.

Megan Mullin, an associate professor of environmental politics at Duke University, thinks it is unlikely for anything climate-related to have a significant impact on the elections, at least nationally. “There’s just too much going on in the political world that’s more immediate,” and the perception people have of climate-related events “is filtered so strongly through their predispositions,” she said.

To date, bad weather events, “even those that can be tied to climate change,” have not seemed to change political conceptions on the issue, said Joseph Majkut, director of climate policy at the Niskanen Center think tank. “I don’t know that that will always be the case,” he said, adding that it is difficult to project what will stick in politics.

Paul Bledsoe, strategic adviser at the Progressive Policy Institute think tank, suspects that the 2017 and 2018 hurricane seasons significantly impacted last year’s midterm elections.

“Extreme weather events caused by climate change affect the overall mood of the country heading into an election, and that can matter, rather than spawning millions of single-issue voters,” Bledsoe said. “It’s more this sense that the sheer scale of natural disasters shows a president not entirely in charge.”

In the June poll, 57 percent of U.S. adults said climate change is being caused by human activity, while about a quarter (26 percent) said it is a natural phenomenon. Five percent said it is not happening, and 12 percent did not know.

The results are consistent with Morning Consult/Politico polling of registered voters in December, which showed 58 percent of adults consider climate change to be primarily human-caused, compared to 30 percent who said it is a natural occurrence.

Jacqueline Toth previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering energy and climate change.

Related content

As Yoon Visits White House, Public Opinion Headwinds Are Swirling at Home

The Salience of Abortion Rights, Which Helped Democrats Mightily in 2022, Has Started to Fade