With the Child Tax Credit, the Unbanked Face Yet Another Trial in Getting Government Benefits

Key Takeaways

Up to 20% of eligible households for the child tax credit may not receive funds via a bank account when disbursement begins in mid-July, per Biden administration estimates.

Democratic lawmakers plan to ask bank executives at hearings this week how they have dispensed funds throughout the pandemic, House and Senate aides say.

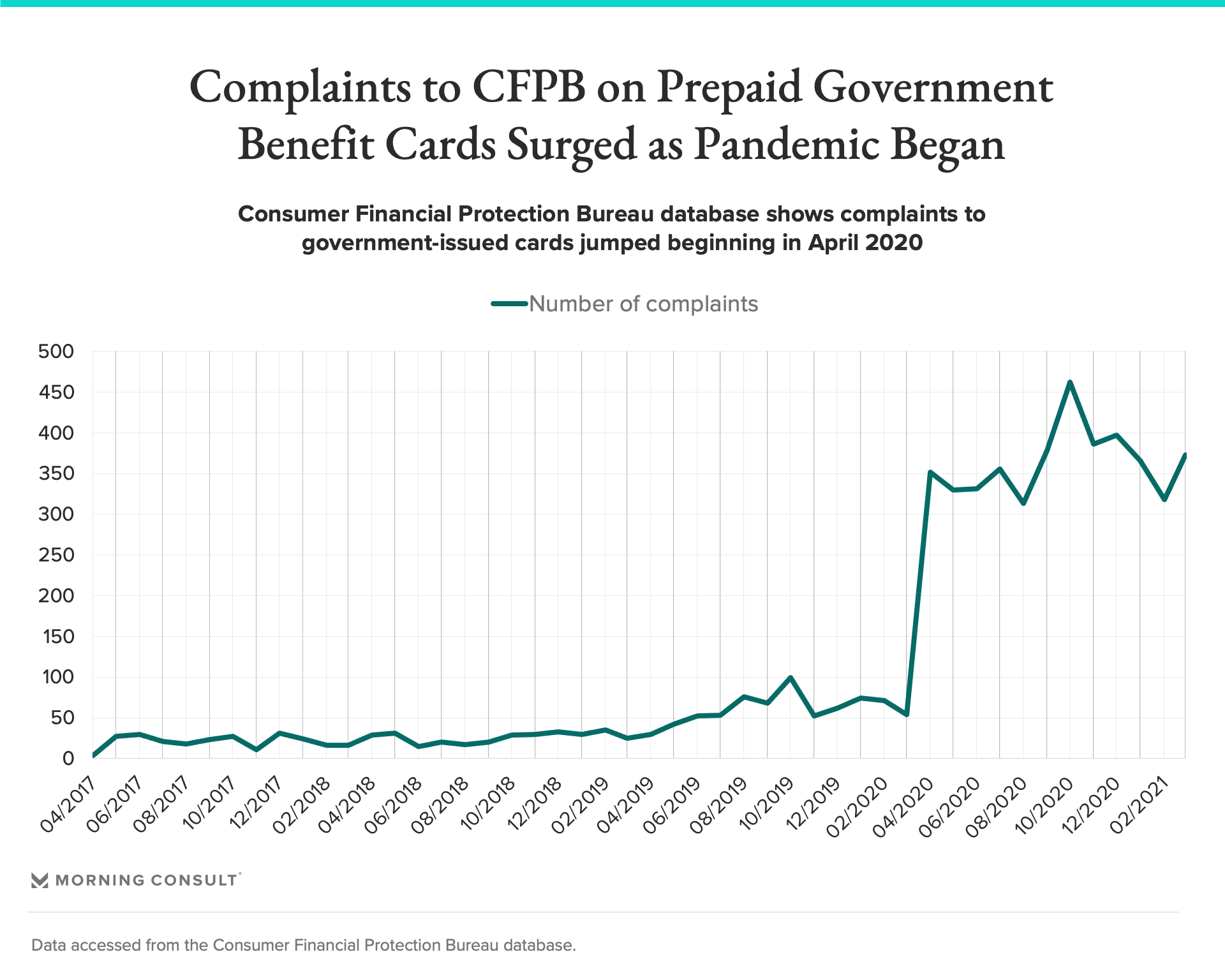

Complaints filed to the CFPB about prepaid government benefit cards have surged during the pandemic, according to the agency’s database.

Trillions of dollars of aid have been sent to U.S. adults since the start of the coronavirus pandemic in the form of stimulus checks and unemployment benefits. That’s put a strain on the often outdated systems that federal governments and states use to disburse money, especially when it comes to unbanked and underbanked Americans.

And now those systems face a new challenge: the child tax credit that’s set to send funds to the families of millions of children in July. While the Biden administration has estimated that 80 percent of eligible households will get that aid directly in their bank account, that still leaves about 1 in 5 who will need to find other methods, such as paper checks or prepaid government benefit cards, to receive the money.

When bank executives appear before the Senate Banking Committee on Wednesday and the House Financial Services Committee on Thursday, Democratic lawmakers are expected to ask about the ways banks have helped disburse money throughout the pandemic, and the issues they’ve had in getting those payments to the right people in a timely manner, according to Senate and House aides.

At the core of the issue is how to get benefits to the unbanked — the people who don’t have access to traditional bank accounts, and who might have issues receiving their stimulus checks and other benefits directly deposited. Research has shown that “unbanked” populations are disproportionately minorities, and are among some of the most vulnerable consumers who need government aid payments to reach their accounts.

From the start of the pandemic, economic stimulus efforts have struggled to reach those Americans who don’t have their direct deposit bank information on file with the Internal Revenue Service, and who don’t get those funds deposited directly into their bank accounts.

Patchy state-controlled unemployment systems have also resulted in inconsistent results for getting jobless benefits across the country. In some states like California, for example, consumers can only get their jobless benefits through prepaid debit cards, which have been plagued by fraud and security issues.

Methods like prepaid benefit cards and paper checks are supposed to help those consumers avoid overdraft fees and allow them to immediately get access to government help. Yet complaints about cards that disburse these benefits, which are used throughout the country -- especially for people who don’t have a bank account -- rose substantially during the pandemic, according to Consumer Financial Protection Bureau data.

Some of the top complaints are from users that have trouble activating or registering the card and the card company not resolving disputes.

To remedy the issue, progressive lawmakers have argued for a public banking option that would offer free and low-cost accounts to all Americans.

Efforts on this front haven’t gone far yet; Reps. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) and Rashida Tlaib (D-Mich.) introduced a public banking bill (H.R. 8721) last year that never made it out of committee. The offices of Ocasio-Cortez and Tlaib didn’t respond to a request for comment on whether they planned to revive the bill this session.

The idea of public banking also faces industry opposition: If consumers have the option of going to a public bank to make deposits, banks wouldn’t have that money to make loans or conduct their business the way they do now, banks argue.

"The way that our banking system works is banks get deposits, those deposits fund loans and there’s a whole ecosystem set up where if you disrupt one piece of it, you disrupt more than you might expect,” said Naomi Camper, chief policy officer at the American Bankers Association.

But while public banking bills haven’t picked up much steam nationally, state-level campaigns have had more success. There’s a public bank in North Dakota, and legislation in some states has made progress or been introduced since the start of the pandemic, with 2021 legislation in Massachusetts, New Mexico, Hawaii, New York, Oregon and Washington.

“This conversation has only come up as the incredible dissatisfaction with regular banks has reached fever pitch,” said David Chiu, a Democratic California assemblymember representing part of San Francisco. “We’ve seen in excruciating detail how our current unemployment system has reflected yet again how the traditional Wall Street banking system has been failing everyday people.”

Chiu co-authored a bill allowing cities and counties to create their own public banks, which was signed into law in 2019. And he’s a co-sponsor of the California Public Banking Option Act, which would establish a public banking option offering no-fee, no-penalty accounts to all California residents.

The financial industry, meanwhile, points to programs like Bank On, a partnership between municipal governments and banks that aims to offer low-cost bank accounts and reduce the number of unbanked consumers.

These kinds of partnerships have been successful in getting people signed up for a bank account, which makes it easier for them to receive government benefits like unemployment, stimulus and in the future, the child tax credit, the industry argues.

“Because the expanded child tax credit payments will recur monthly, it’s an especially important moment to get people into bank accounts and enrolled in direct deposits,” Camper said. “Getting more people into the banking system could be one of the silver linings from this pandemic.”

Advocates of open banking legislation, like Chiu, say that programs like Bank On don’t address core issues in unequal access to banking services (distrust among minority communities, for example), and that a more holistic solution is needed.

Despite the political difficulties facing public banking efforts on a national level, Aaron Klein, a senior fellow in economic studies at the Brookings Institution who focuses on financial technology and payments, said that less ambitious solutions could have a big impact on getting money out via the child tax credit.

Government partnerships with fintech companies that can reach a broader base of consumers’ “financial address” via real-time payments -- not only through tech -- would get more aid to people immediately, he said. Although Klein noted that there are longstanding bureaucratic issues at the Treasury Department and the Federal Reserve that make implementing these solutions tricky.

“We can solve this problem with all the tech that exists,” Klein said.

Claire Williams previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering finances.