With More Than 80% of Gen Z Students Attending Classes Remotely This Semester, 'Falling Behind' Concerns Abound

Key Takeaways

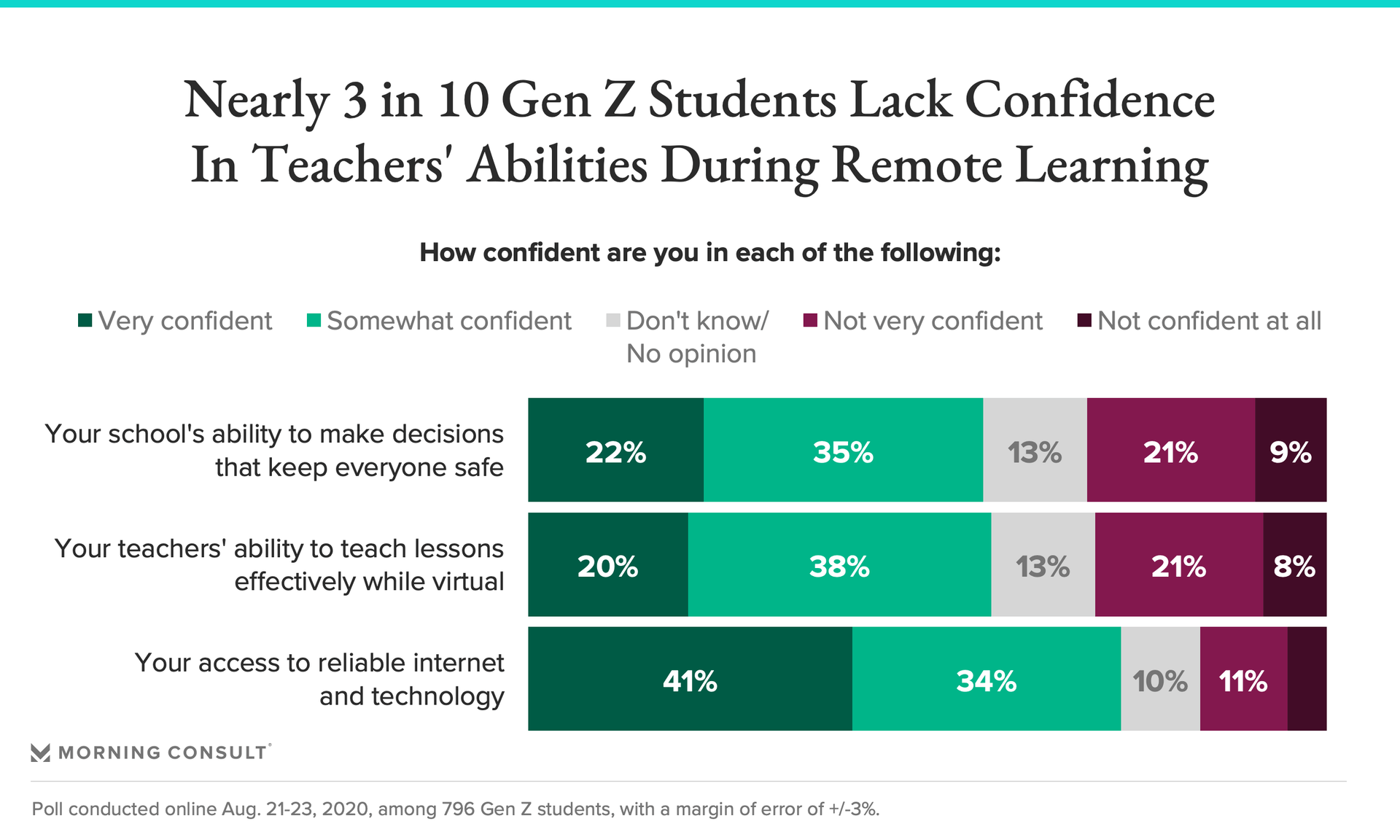

29% are either “not very confident” or have no confidence at all in their teachers’ ability to effectively instruct online this fall.

66% of those attending school online said they were at least “somewhat confident” in their school to make decisions that will keep them safe; 56% of those who are attending class partially in-person and remote said the same.

For Keegan Walker, the only good thing about logging into his seventh-grade classes remotely during the first couple days of school this week has been the absence of the backpack he’d have to lug around.

But his list of benefits ends there.

With the threat of COVID-19 forcing his middle school in Virginia Beach, Va., to continue with online-only instruction for now, Walker, 12, is back to staring at his computer screen nearly non-stop from 8:55 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday and worrying about only being able to contact his teachers through email if he has a question about an assignment. “I personally don’t really like the schedule of school at the moment,” he said. “It’s weird.”

And Walker has plenty of company in navigating the new school-day regime.

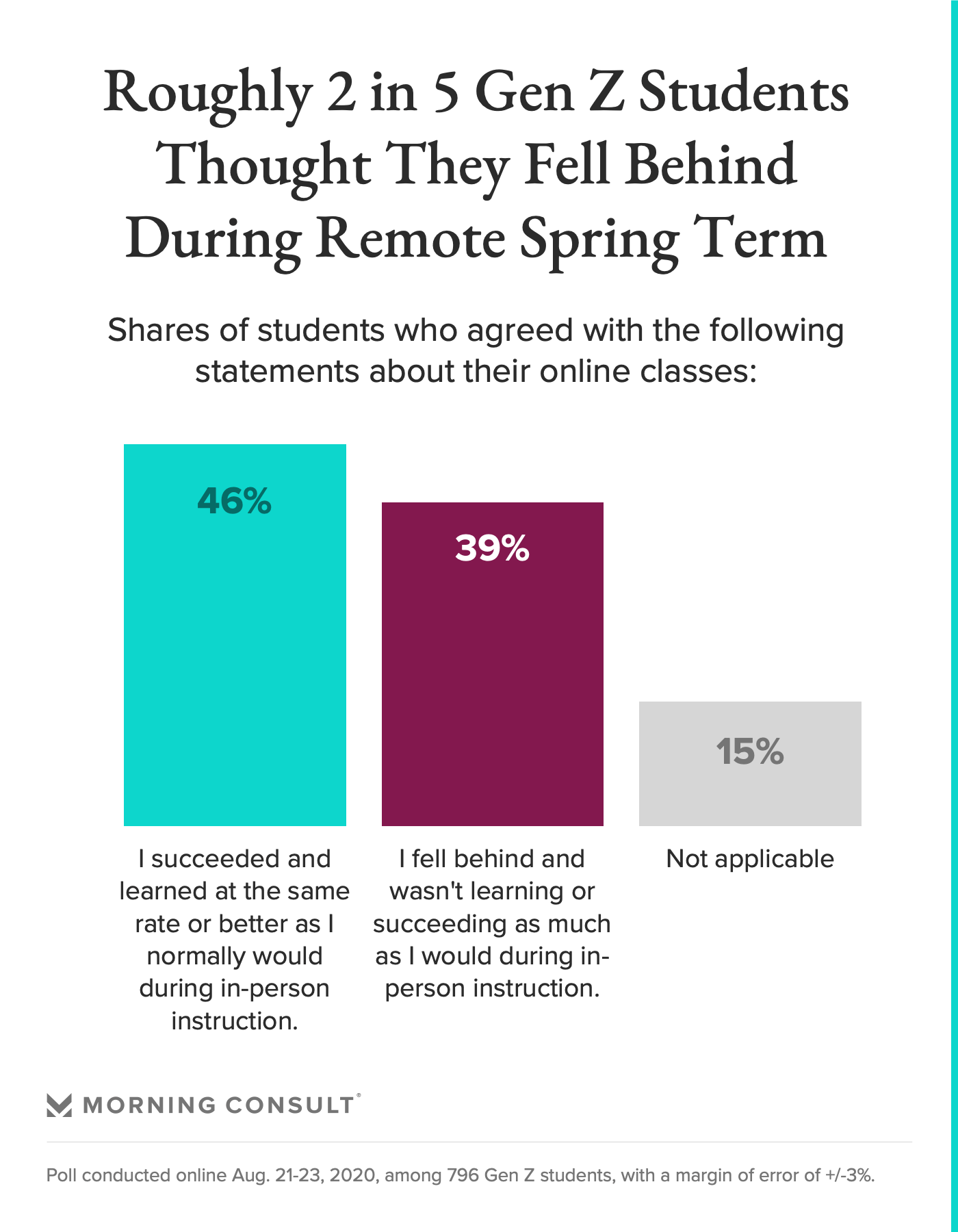

According to a recent Morning Consult survey, 83 percent of Gen Z students said they were either attending classes completely or partially remote this semester. And although many of these students got their first experience with remote learning in the spring semester, they were relatively split on how well they performed during those online classes.

Thirty-nine percent of Gen Z students said they felt like they “fell behind” in the spring when their classroom went virtual and that they didn’t learn or succeed as much as they normally would through in-person instruction. In contrast, 46 percent said they felt they performed the same or better in the same setting. While more than half of these students said they had faith in their teachers’ ability to instruct effectively in a virtual classroom this fall, 29 percent are either “not very confident” or have no confidence at all in their teachers’ capabilities in a remote setting.

The survey, which was conducted online from Aug. 21-23 among 796 students between the ages of 13 and 23, has a margin of error of 3 percentage points.

The failure to contain COVID-19 throughout the United States has forced many school districts to incorporate remote instruction into their school days this fall. And the pandemic has thrown a spotlight on how underprepared the education system was for everyone to go digital, with some students struggling to find reliable at-home internet and teachers quickly working to learn how to make the most of what online instruction has to offer.

“Not all online learning is the same, and online learning can be really great,” said Matt Rafalow, a sociologist and visiting scholar at the University of California, Berkeley. “Only really when teachers feel safe and supported for online learning can we really start having conversations about what a better, more connected and engaging online pedagogy can look like.”

The Morning Consult survey also included an open-ended question where students were asked to describe their main concern with remote learning this semester.

While a plurality (25 percent) said they had no concerns or weren’t sure, 1 in 5 focused on whether their teacher will disseminate information effectively and questioned their own ability to retain new material.

“Remote learning isn’t for everybody. Some people aren’t capable of learning online and some don’t have the resources,” one respondent said. “However, I don’t believe most schools are taking the proper precautions or realizing the traumatic effects the pandemic has caused some students.”

Fourteen percent expressed concerns about their ability to focus while online, and 13 percent were concerned about the lack of in-person interaction.

And 11 percent were concerned about issues regarding technology, such as at-home internet access, glitches and whether their teachers could work the video platform. One Gen Z respondent said, “If you have bad internet they won’t care and just let you fail because you can’t hear what the teacher says with lag.”

Rafalow also said that, because the survey was conducted online, it’s most likely missing the student population that lacks reliable technology and at-home internet. In the survey, 75 percent of students said they were confident in their access to reliable internet and tech this year. However, Rafalow points out that he’s heard plenty of stories about students having to sit in the parking lots of fast food restaurants or libraries to get a Wi-Fi signal for their classes.

Michele Oger, a mother of two teenagers in Westfield, Ind., said in an interview that finding a balance between in-person socialization and personal safety was the main reason her family chose to send her kids to school in-person twice a week when given a choice between that and doing everything remotely. Students in the Westfield Washington school district who opt for the hybrid model go into the school building in shifts: Those with last names A through L attend classes in-person Mondays and Wednesdays, while those in the latter half of the alphabet go Tuesdays and Thursdays. Fridays are set aside for sanitization.

But that split in the alphabet has negated the social benefits Oger’s son, who’s in 10th grade, would’ve had because most of his friends have last names earlier in the alphabet. And the days they’re home are set aside as personal work days, not additional online classes, so the student groups never cross paths -- even virtually.

Now, Oger’s family is debating whether they should switch to the online-only option in the next trimester in November -- the earliest they can change the way their children attend classes.

“For their health, that may be what we end up doing,” she said, adding that the health risk could increase in the colder weather and amid the flu season.

While remote instruction has its drawbacks, students who are fully online tend to have more confidence in their schools to make decisions about instruction that prioritize safety: 66 percent of those attending school online full time said they were confident in their school or university administration’s decisions to keep everyone safe, while 56 percent of those who are attending partially remote and partially in-person said the same.

However, in order for complete online instruction to be effective, teachers need to be better prepared and given the space to learn how to best use the technology at their disposal, which school districts that made last-minute decisions to be remote didn’t give them, Rafalow said.

While a number of schools offered their teachers online education trainings over the summer, not all teachers have fully adjusted to remote learning. Walker, the seventh-grade student in Virginia Beach, said that although his classes only started Tuesday, so far his teachers appear to be sticking to the same teaching style they conducted in-person: mostly lectures and presentations, just on Zoom, with minimal opportunities to work in groups.

Rafalow said that’s a missed opportunity. If they had been better prepared, teachers could be turning to remote education techniques, such as Zoom’s breakout room feature, which breaks up the class into small groups so they still have an opportunity to interact with one another, or the chat feature in video platforms.

As Oger’s family contemplates a potential switch to remote-only education later in the year, she said she sees the value in all students having the same opportunity to avoid in-person instruction if they don’t feel safe -- especially if the teaching styles in online-only instruction became more interactive.

“Psychologically, you're going to have a lot of families that are not going to want to come out of their homes or return to public schools,” Oger said. “Having a nice, true online platform is something, as a nation, we need to work towards.”

Sam Sabin previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering tech.

Related content

As Yoon Visits White House, Public Opinion Headwinds Are Swirling at Home

The Salience of Abortion Rights, Which Helped Democrats Mightily in 2022, Has Started to Fade