How Miss America’s Swimsuits Are Really About Politics, Not Gender

Key Takeaways

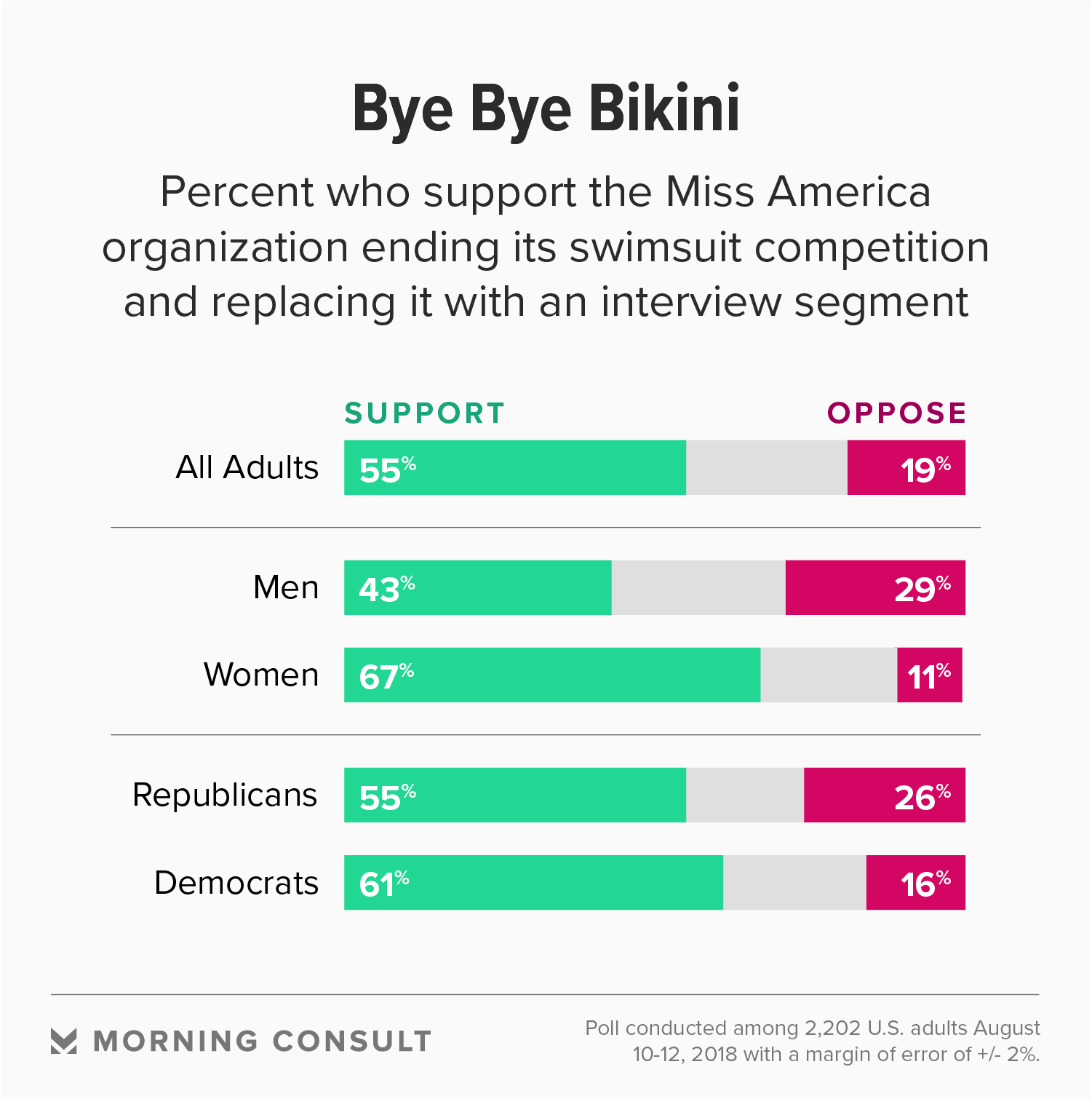

55% of U.S. adults back the decision to kill the swimsuit contest in Miss America, while 19% are against it.

51% of the public thinks women exploiting their sexuality has become as big a problem as men objectifying women, an issue that creates partisan divides: 66% of Republicans versus 44% of Democrats agree.

For the first time in its nearly 100-year history, Miss America will not formally judge its candidates on their physical appearance when the pageant runs next month. And it’s a move the public largely applauds, according to new polling.

The Miss America Organization announced in June it was saying #ByeByeBikini and eliminating the swimsuit portion of its competition, along with revamping the judging of its evening wear portion to solely focus on candidate’s interview responses.

Fifty-five percent of respondents in the Aug. 10-12 Morning Consult survey said they supported the Miss America Organization’s decision to end its swimsuit contest, while 19 percent were opposed.

Women, intuitively, were more likely to applaud the end of judges’ scoring of women on how they look in swimsuits: More than two-thirds (67 percent) were behind it compared to 43 percent of men. Nearly three in 10 men (29 percent) didn’t support the move.

The Miss America Organization “is allowing candidates to define their beauty through their accomplishments, their ability to command attention and defend their opinions,” a spokesperson told Morning Consult in an email this month. “We don’t feel young women of today should have to walk around in four inch heels and a bikini to exhibit their intelligence, talent and what they want to do with the job of Miss America in advancing their own personal social impact initiative.”

But not everyone is cheering these changes.

Four of the nine members of the Miss America Organization board quit or were forced to resign this summer, reportedly over the demise of the swimsuit portion of the competition. Around the time this news was reported, 22 leaders from state-level pageants and the District of Columbia called for a vote of no confidence in new chairwoman Gretchen Carlson and the resignation of president and Chief Executive Regina Hopper and the entire Miss America board over the direction of the organization.

Indeed, although most Americans support the move away from the bikini contest, public responses on deeper questions about female objectification and sexual exploitation start to get more complicated. And experts dismissed the idea that removing formal scoring for appearance meant Miss America contestants wouldn’t be judged on their looks.

Miss America credits itself as a “disruptor” for women -- and that’s certainly how it started. The idea of women in the 1920s walking down the boardwalk in a bathing suit was quite progressive, said Blain Roberts, history professor at California State University, Fresno, and author of “Pageants, Parlors, and Pretty Women: Race and Beauty in the Twentieth-Century South.”

“On the whole, if you take the long arc of the history of the pageant, they have been slow to change,” she said in an interview this month. “And they have been reactive rather than proactive in terms of improving the status of women and, of course, working against the objectification of women.”

“What happened is that the slightly rebellious nature of showing your body in public, over time, becomes compulsory,” she said.

With that, the meaning of the pageant changed to be less about progressive sexuality and more about the objectification of the female form, Roberts said.

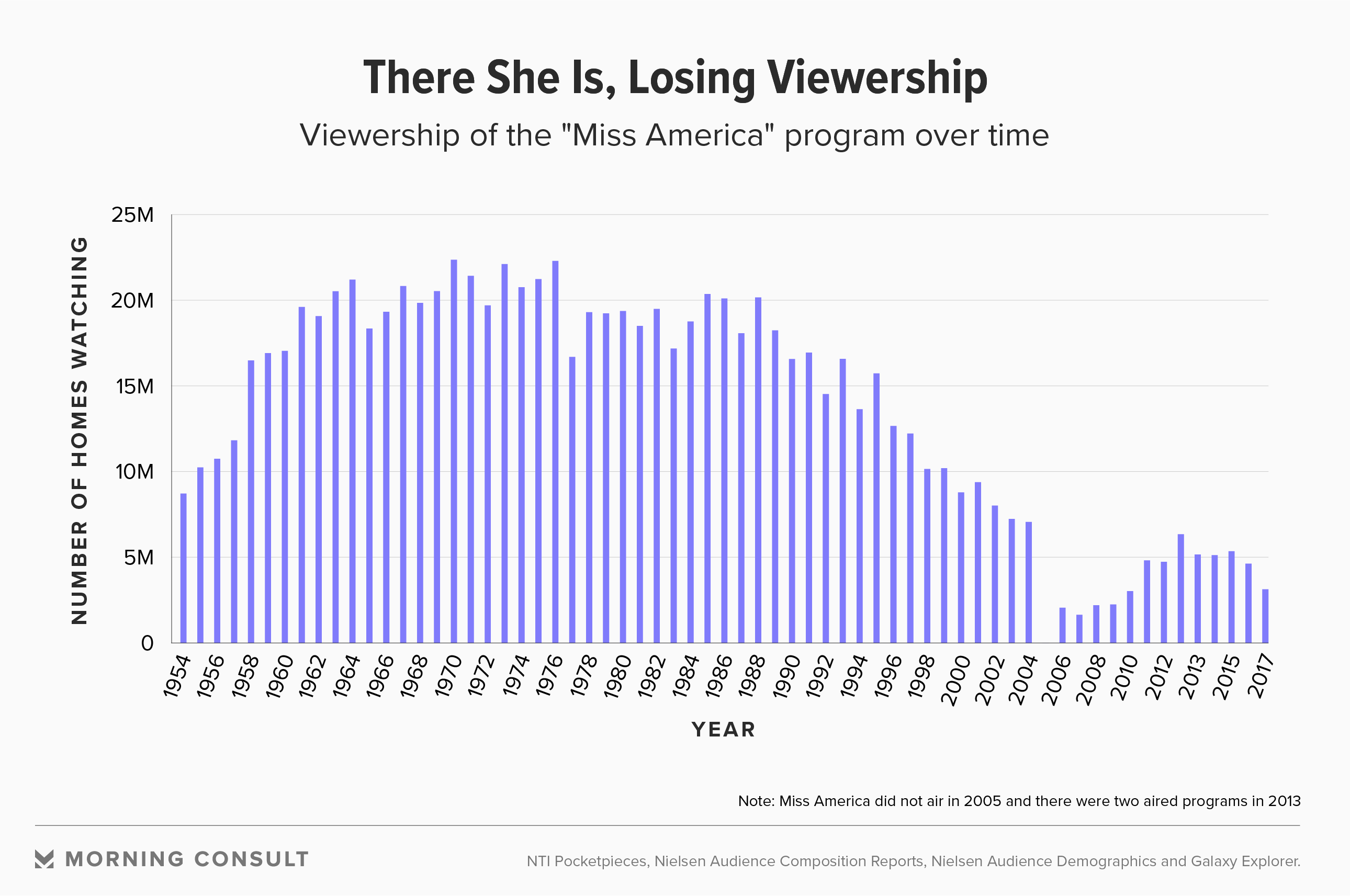

Miss America’s viewership has plummeted since the 1970s. Roberts attributed this partly to changing attitudes on the objectification of women -- and on beauty pageants, which led to a decline in Miss America’s cultural relevance. Experts said media fragmentation has also played a role.

But Hilary Levey Friedman, a professor in Brown University’s department of education and author of the forthcoming book “Here She Is: Beauty Pageants and the American Woman,” said falling Miss America viewership doesn’t mean that Americans have turned away from similar television content, pointing to the televised Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show and programs such as “Bachelor in Paradise,” in which contestants appear in bikinis most of the time.

If consumers want to watch scantily clad women on television, they have no shortage of material.

And more skin didn’t necessarily help Miss America’s cause: In 1997, in the midst of falling numbers of viewers, the organization started allowing women to wear two-piece swimsuits on stage. Their viewership continued to fall.

Men are more likely than women to say the new, swimsuit-less Miss America program makes them less likely to tune in: 21 percent vs. 7 percent. Pluralities of both men and women said the announcement wouldn’t shift their decision to watch either way. The survey was conducted among 2,202 U.S. adults and has a margin of error of 2 percentage points.

Under the pageant’s previous guise, Miss America candidates’ appearance -- how they performed in the swimsuit and evening wear segments -- accounted for 35 percent of their score in preliminaries and a quarter on the final judging night.

Carlson, the board’s chair, is seen to be crucial in the decision to ax swimwear and launch what she calls “Miss America 2.0”; she was elected to her current role in Miss America in January, after previous CEO Sam Haskell resigned following leaked emails of him vulgarly describing former contestants.

Carlson became an important figure in the #MeToo movement when she filed a sexual harassment lawsuit in 2016 against her former boss, the late Fox News chairman Roger Ailes.

At an event at the National Press Club, Carlson said the organization changed the competition to “accurately reflect today’s modern-day woman,” especially in light of the #MeToo movement, by changing the rules to no longer judge women by physical appearance.

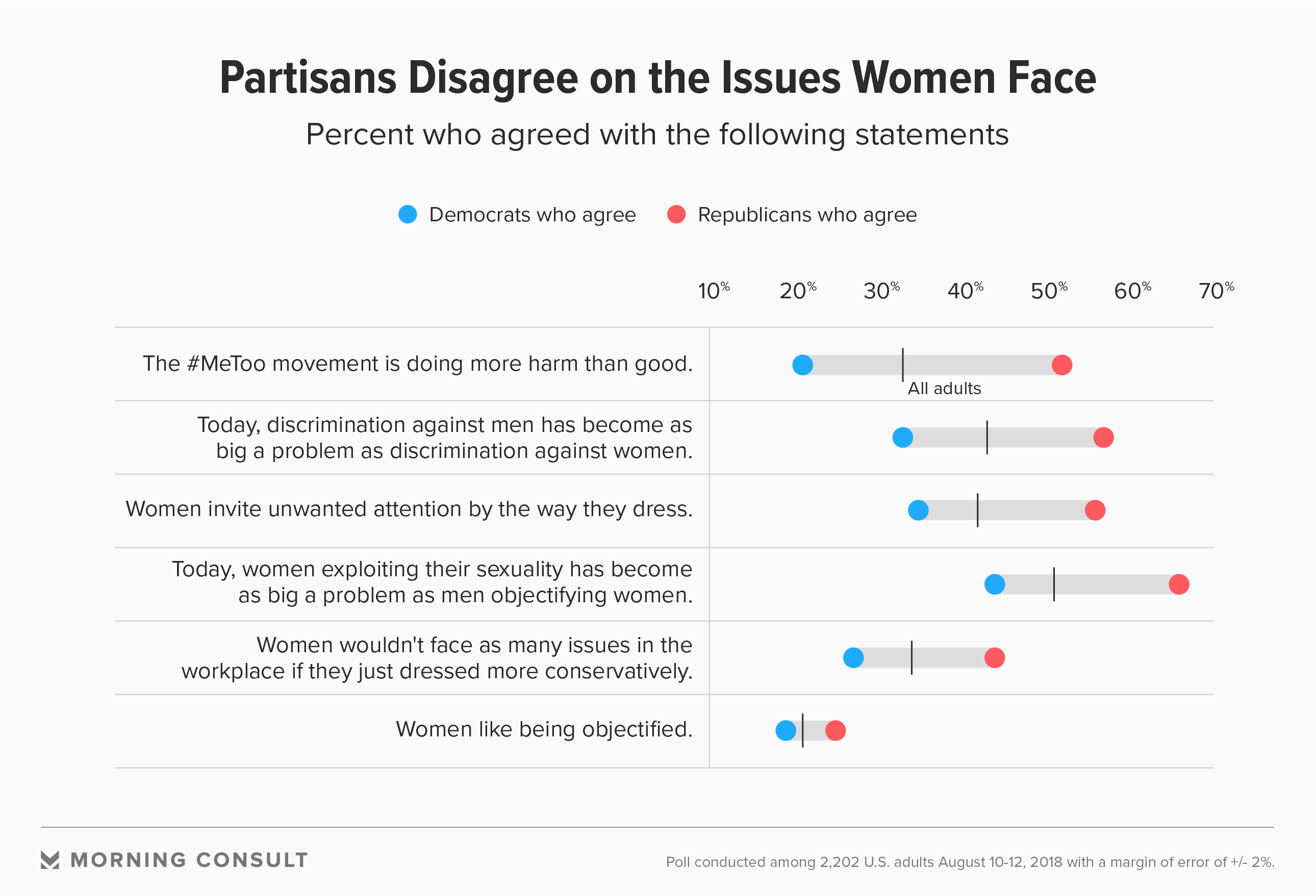

Americans were split by political party, not gender, when it came to broader questions about women’s appearance and sexualization.

The public was divided, 37 percent to 30 percent, on whether the Miss America competition sets a good example for young women; another 34 percent didn’t know. Republicans were 10 points more likely than Democrats to say the competition does a good job of setting an example for young women (46 percent vs. 36 percent).

Majorities of Republicans agree with statements such as “Today, women exploiting their sexuality has become as big a problem as men objectifying women” (66 percent); “Women invite unwanted attention by the way they dress” (56 percent); and “The #MeToo movement is doing more harm than good” (52 percent).

That’s at least 20 points higher than Democrats’ responses to each statement.

In contrast, gender breaks were more muted. The statement saying that sexual manipulation is as big a problem as objectification, for example, only elicited a 3-point gap in agreement between men and women (50 percent to 53 percent), while it created a 22-point gap between Republicans and Democrats.

Political conservatives have a more traditional view of gender roles and how men and women are supposed to behave, Roberts said.

Notably, nearly three quarters (73 percent) of Republican women agreed that women capitalizing on their sexuality was as big an issue as men objectifying females, 15 percentage points higher than what Republican men said (58 percent) and 22 points higher than all adults (51 percent).

The Miss America Organization spokesperson said the group is not involved in the political sphere and that “the advancement of young women’s education and their service to their country and communities is certainly bi-partisan.”

Yet according to Levey Friedman, there’s a seed of conservatism within the aesthetics of Miss America, and pageants overall, in how some of the contestants present themselves; the fake eyelashes, big hair and ball gowns adopt a more traditional approach to womanhood.

And for parts of this audience, removing the swimsuit portion of the program isn’t necessarily a nod toward the modern woman.

“Some might see it as the negation of the tradition,” she said in an interview this month.

Joanna Piacenza leads Industry Analysis at Morning Consult. Prior to joining Morning Consult, she was an editor at the Public Religion Research Institute, conducting research at the intersection of religion, culture and public policy. Joanna graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Madison with a bachelor’s degree in journalism and mass communications and holds a master’s degree in religious studies from the University of Colorado Boulder. For speaking opportunities and booking requests, please email [email protected].

Related content

As Yoon Visits White House, Public Opinion Headwinds Are Swirling at Home

The Salience of Abortion Rights, Which Helped Democrats Mightily in 2022, Has Started to Fade