The IOC Loosened Its Policy on Olympic Athlete Protests. Polling From 5 Countries Suggests They Got It Right

Key Takeaways

40% of U.S. adults said the policy preventing post-competition demonstrations is “appropriate.”

At 17%, U.S. adults were more likely than those in other polled countries to say the policy is “too permissive.”

At 22%, Mexican adults were most likely to say the policy is “too restrictive.”

Heading into the Tokyo Olympics, how the International Olympic Committee would respond to a violation of its policy limiting athletes’ political protests was always a matter of “when,” not “if,” such a violation took place.

That moment came Sunday when American shot-putter Raven Saunders raised and crossed her arms in an “X” — a symbol of support for oppressed people like herself, she explained — while standing on the podium following her silver medal-winning performance.

Mark Adams, director of communications for the IOC, told media yesterday that the committee had requested information from the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee about Saunders’ demonstration in order to determine “next steps, if any, that should be taken.” The U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee had previously issued a statement saying Saunders’ demonstration didn’t violate any of its rules, which allow for peaceful protest, meaning any discipline would likely come from the IOC alone.

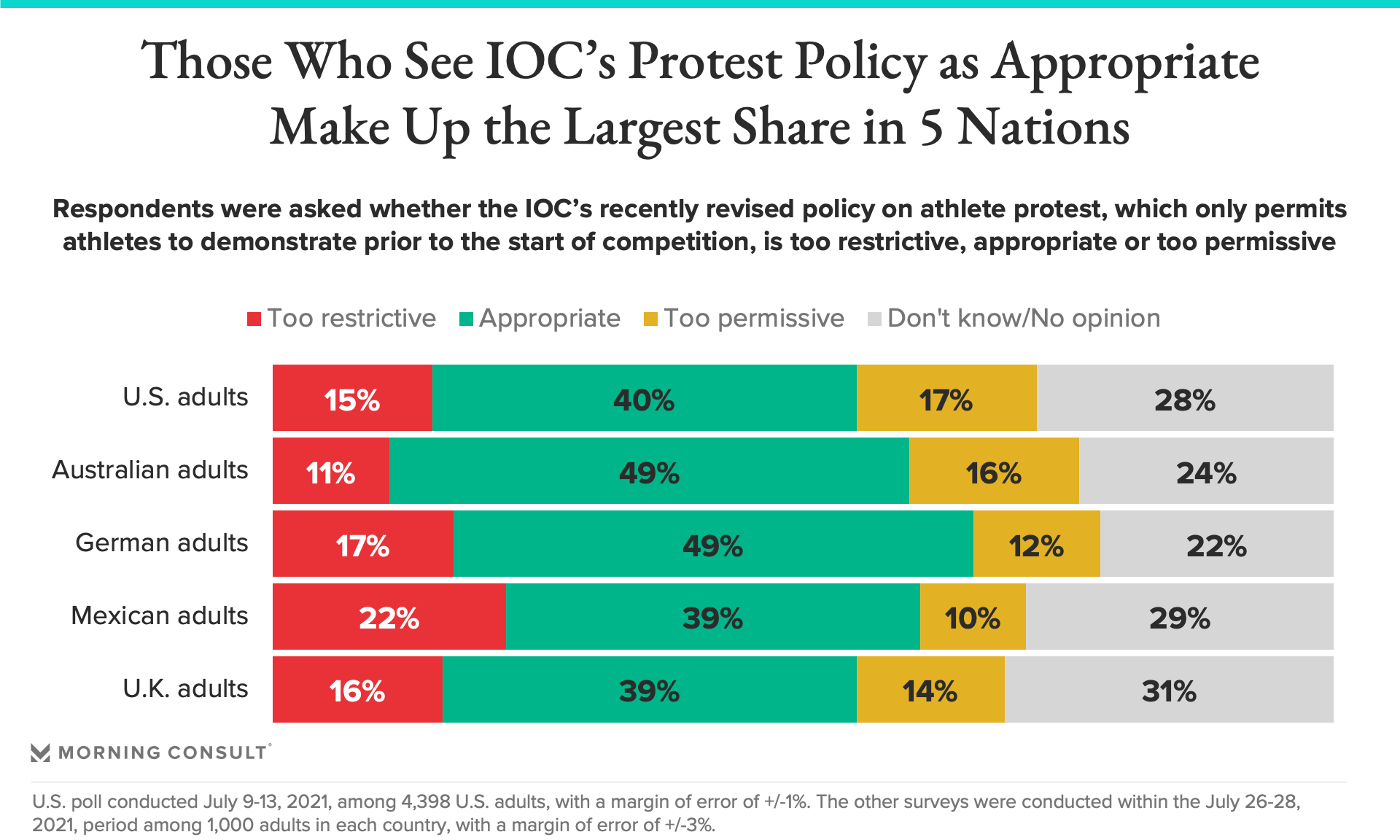

Morning Consult data shows that a plurality of adults in five countries -- the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, Germany and Mexico -- believe the IOC’s recently revised policy on athlete demonstration is “appropriate.” The loosened guidelines, released in early July, permit athletes to demonstrate prior to the start of the competition, but they still restrict athletes from protesting during competition or during Olympic ceremonies, such as the opening and closing ceremonies or medal presentations.

A Morning Consult survey of 4,398 U.S. adults prior to the start of the Tokyo Olympics found that 40 percent of respondents viewed the policy as appropriate, while 17 percent felt it was too permissive and 15 percent felt it was too restrictive.

In subsequent polls of 1,000 adults per country, 39 percent of U.K. and Mexican adults said the policy was appropriate, along with 49 percent of Australian and German adults.

U.S. and Australian adults were most likely to say the policy was “too permissive” of athlete demonstration at 17 percent and 16 percent, respectively. Mexican adults were the most likely to say the policy was “too restrictive” at 22 percent.

Following her demonstration, Saunders, who is Black and a lesbian, said the “X” represented "the intersection of where all people who are oppressed meet." Also on Sunday, U.S. fencer Race Imboden drew an X on his right hand that was visible as he accepted a bronze medal, though it doesn’t seem that incident drew the attention of the IOC.

Debate about whether sport is an appropriate platform for political demonstration has been a hot-button issue for years in the United States but has taken on newfound intensity since an outpouring of demonstration from athletes and sports organizations following the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis last year.

Athlete demonstrations have made international headlines in recent months as well. In late June, German and British soccer players took a knee at the popular Euro 2020 tournament to protest racial inequality. The women’s soccer teams of Britain and Chile also took a knee last month for the same reason before their opening Olympic match.

Prior to the IOC’s recent revision of its policy, competitors were prohibited from demonstrating in any way at any point during the games. In a May survey, U.S. adults were more likely to support the IOC’s protest ban than to oppose it, reflecting a broad desire to keep politics out of sport.

Alex Silverman previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering the business of sports.

Related content

As Yoon Visits White House, Public Opinion Headwinds Are Swirling at Home

The Salience of Abortion Rights, Which Helped Democrats Mightily in 2022, Has Started to Fade