Regulators Want to Extend Some Pandemic Telehealth Flexibilities. Virtual Care Companies Still Have Questions

Key Takeaways

Federal regulators have proposed extending some telehealth flexibilities for behavioral care through at least the end of 2023.

Virtual care companies want clarity on providers’ ability to offer telehealth services across state lines, pay parity and other regulations beyond the pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic reshaped the way many Americans get health care, largely by ushering in new flexibilities that made telehealth easier to access. Now, as policymakers wrestle with which pandemic-induced changes have staying power beyond the crisis, providers are insisting virtual care is here to stay — and pleading for clarity as they chart their own paths forward.

On Monday, a group of 430 health care and technology groups asked lawmakers to address the “telehealth cliff” they say is looming at the end of the public health emergency. Medicare officials are proposing extending waivers to keep some telehealth services easier to access through 2023, and while that offers some stability over the next 18 months, the future of the field — including coverage, what types of virtual care will be offered and how people will be able to access services — is still very much in flux, and the uncertainty has thrown a wrench into how telehealth companies are planning for their futures.

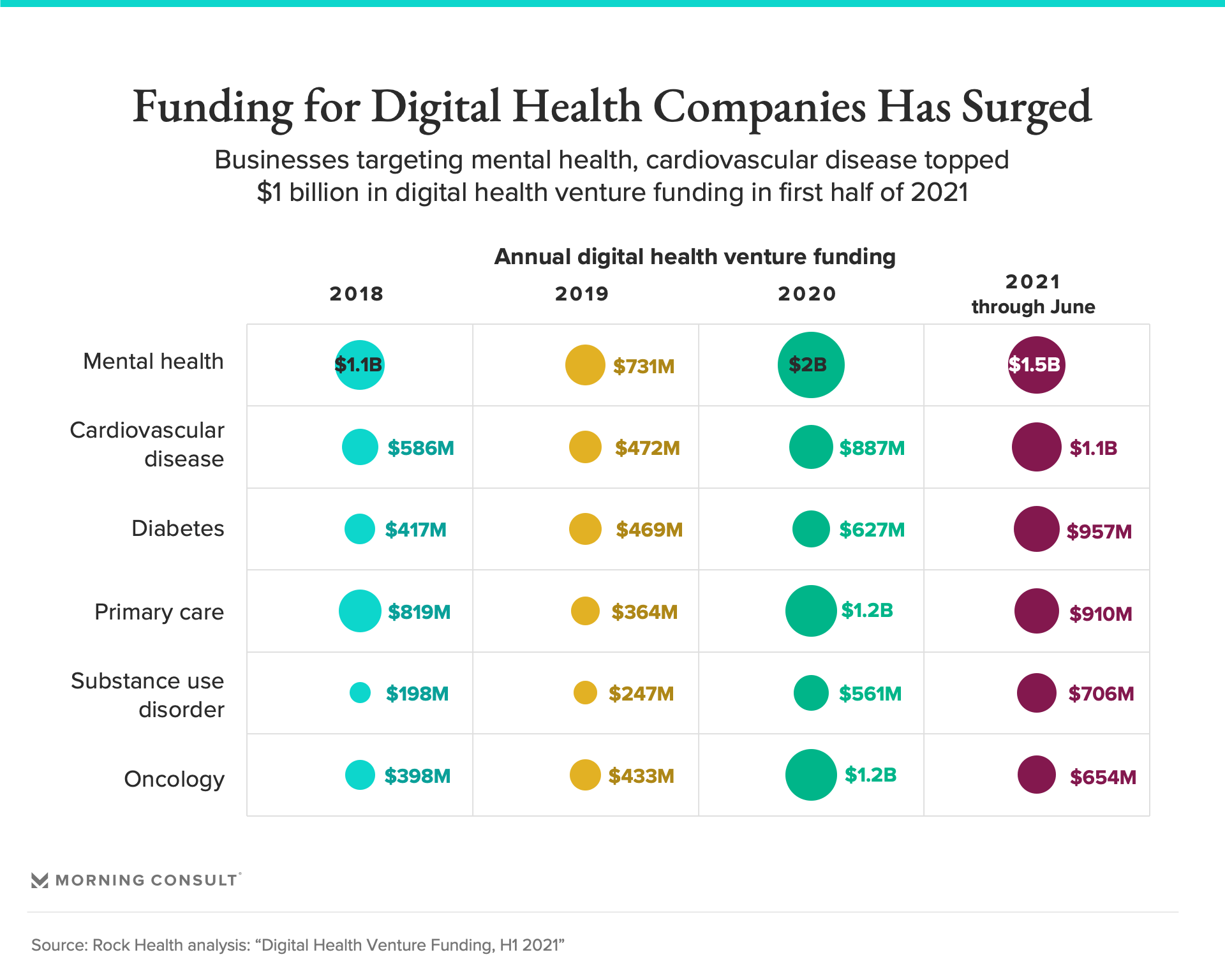

It’s happening even as the digital health sector is seeing its biggest boom ever, securing a record-high $14.7 billion in funding in the first half of 2021, according to Rock Health, a venture fund focused on digital health startups. Telehealth use has also surged over the past year, peaking in April 2020 but remaining 38 times above pre-pandemic levels as of February, a McKinsey & Co. analysis found.

“We built this system to operate in a complex environment prior to the pandemic, so we can continue to operate after,” said Russell Glass, chief executive of Ginger, which provides on-demand mental health care to companies. But, he said, reverting back to the pre-pandemic telehealth environment “doesn't mean it's good for the consumer.”

That’s largely because regulators have allowed mental health clinicians to practice telehealth across state lines during the public health emergency. But the Biden administration has been extending the emergency order in 90-day increments, meaning the waiver could be revoked with little notice, disrupting patients’ relationships with therapists and other behavioral health providers.

“It gets extremely murky in terms of being able to understand what the laws are, and what they're going to be,” Glass said. Federal health officials have signaled they expect the public health emergency to last through the end of 2021. But the short-term forecast “just doesn't give providers enough time to plan,” he said.

Executives at Talkspace Inc., a virtual behavioral health care company, and Teladoc Health Inc., which offers primary care, mental health services and other telemedicine, also highlighted the importance of keeping cross-state licensing in place after the pandemic.

“Extending the waivers will ensure that trusted patient-provider relationships that take place across state lines are not severed,” said John C. Reilly, Talkspace’s general counsel. Those relationships are why the company believes virtual mental health services should be considered separately from other forms of care as policymakers weigh waivers and other extensions on telehealth use, he added.

In the meantime, Talkspace is hiring hundreds of therapists and helping them get licensed in multiple states so they can help meet the demand for mental health services in areas with care shortages, Reilly said.

Meanwhile, Claudia Duck Tucker, senior vice president of government affairs at Teladoc Health, said that while commercial health plans and employers are looking to expand their telehealth offerings, “there is much less certainty from Congress and some state legislatures” on what services could be available to those who are insured through Medicare and Medicaid once the pandemic ends.

“This could result in those who work for the right employers or have the right health plans enjoying significantly better options and access to care than Americans, for example, in traditional Medicare,” Tucker said.

Another key question for telehealth companies is whether virtual visits will be reimbursed at the same level as in-person care.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services offered some insight into how it views the future of telehealth in a proposed rule issued this month. Under the rule, providers offering mental health care via telehealth would be required to hold in-person visits with patients every six months, and it would also limit the use of audio-only visits.

The agency, which is soliciting feedback on the proposal until mid-September, declined to comment on the proposed rule, but a spokesperson said that "telehealth remains a critical component of CMS’s priorities, particularly in the battle against COVID-19." Some companies are already raising concerns about the restrictions, arguing they could upend operations and limit reimbursement for mental health providers offering virtual-only care.

Even as policymakers “are looking for ways to reduce health inequities, they instead have chosen to impose additional barriers to mental health access which will discourage treatment,” said Latoya Thomas, director of public policy and government affairs at telemedicine company Doctor On Demand Inc., which merged with Grand Rounds Health Inc.

Other companies are forging ahead with their plans to expand telehealth offerings despite the uncertainty, betting that telehealth will be too cumbersome for policymakers to rein in once it’s fully integrated into patients’ care. For example, Optum Health, UnitedHealth Group Inc.’s health tech services business, has seen more than 500,000 virtual visits on its behavioral health platform this year, according to the company’s latest quarterly earnings report.

“We’re really just grabbing the reins and staying focused on what our patients need, what our members need and what our clinicians need, and then working to advocate for the necessary changes to make that a reality at scale,” said Kristi Henderson, Optum’s senior vice president of telehealth and innovation.

Even so, the uncertainty about what policymakers will do once the public health emergency ends, as well as the variability across states, has made it difficult to plan. Regardless of how policymakers decide to regulate telehealth going forward, virtual care companies said they need some answers — the sooner the better.

“As we build all of this, we’re looking at creating this digital gateway into the health care system,” Henderson said. “And so awareness and stability, from a regulatory perspective, is going to be incredibly important.”

This story has been updated with comment from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Gaby Galvin previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering health.