Spurred by COVID-19 Pandemic, Pharmacy Giants Boost Health Care Ambitions

Key Takeaways

Pharmacy chains are betting on a combination of digital and in-person services as they bolster their health care presence during the COVID-19 pandemic.

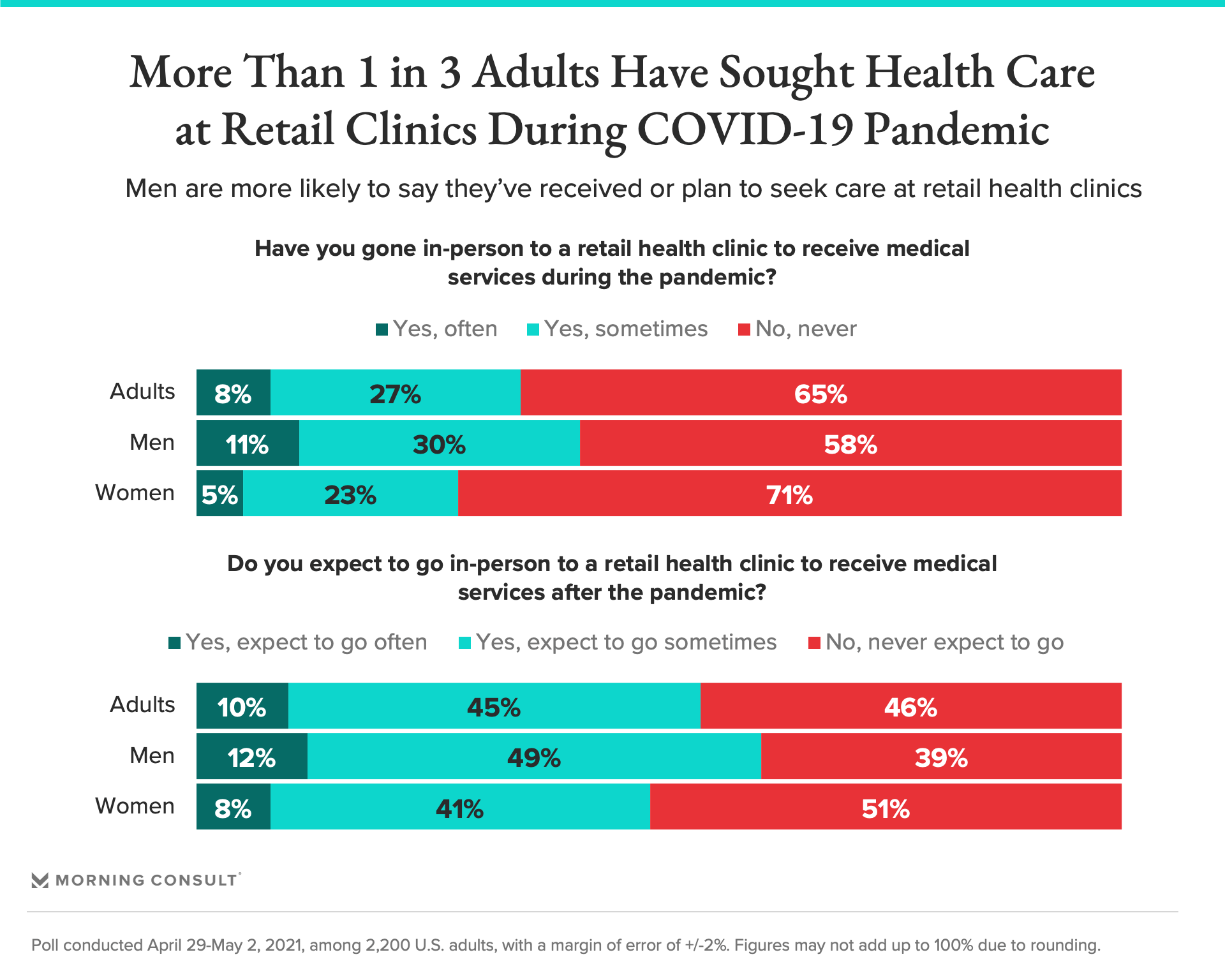

35% of adults say they have received health care at a retail clinic during the pandemic, while 55% say they plan to seek care there in the future.

Just in the past week, CVS Health Corp. announced an employer-based COVID-19 vaccination program, an expansion of community-based screenings for early diabetes and high blood pressure indicators, a women’s heart health initiative and a $100 million fund to invest in digital health.

But the retail pharmacy giant, along with competitors Walgreens Boots Alliance Inc. and Walmart Inc., has been inching into the $3.8 trillion health care space for years. Taken together, the chains’ most notable moves have been to launch health clinics, partner with insurers and explore digital health tools -- and their window into health care has only widened during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Millions of people have gotten tested and vaccinated at the major drugstore chains, and executives and market analysts say the COVID-19 effort represents an opportunity to reach new patients and cement their role in the crowded health care field. Traditional providers, they say, should be worried.

When patients have a choice about where they receive health care, the “golden rule” is “cost, quality and convenience,” said James Beem, managing director of global health care intelligence at J.D. Power. “And those retail pharmacies offer that.”

Even before the pandemic, retail clinics’ collective health care footprint was growing. A FAIR Health Inc. report found that retail clinic use rose 39 percent from 2018 to 2019. And early data indicates this shift has continued: 35 percent of adults said they received care at a retail health clinic during the pandemic, while 55 percent said they plan to do so in the future, according to a new Morning Consult survey.

The pandemic has “accelerated the impetus for creating those local, more convenient access points for health care,” said Christopher Cox, senior vice president of pharmacy at CVS Health, which hopes to facilitate 65 billion health care interactions by 2030.

At CVS, more than half of COVID-19 vaccinations have been among people who were not existing pharmacy patients, Cox said, representing “an opportunity for us to have people say, 'Wow, I hadn't thought of CVS before, but that was an awesome experience.’”

During an earnings call Tuesday, company leaders said 9 percent of customers who came to CVS through COVID-19 testing have filled a new prescription at its pharmacy, while customers there for vaccine appointments are “more actively shopping” at the drugstore, despite lower overall foot traffic during the pandemic.

CVS also launched a new telehealth service via its Minute Clinics last year, and is piloting a mental health counseling program in its stores as it considers how to address the mental health toll of the pandemic. Some of its roughly 800 HealthHUBs even have licensed social workers, CVS President and Chief Executive Karen Lynch said on the Tuesday call.

The company is pushing policymakers to allow pharmacists to “practice at the top of their license” by granting them flexibility to help manage patients’ chronic conditions in addition to filling their prescriptions, a shift that’s already taken place during the pandemic, Cox said.

That idea has gained some traction on Capitol Hill: Last month, Sens. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa), Bob Casey (D-Pa.) and Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) reintroduced legislation that would allow Medicare to pay for health services provided by pharmacists in states where they’re licensed to offer them.

Beyond the care it provides directly to patients, CVS also plans to leverage its COVID-19 testing infrastructure to identify and recruit potential participants for clinical trials testing potential future vaccines and treatments.

Competitor Walgreens is also banking on an expanded role for pharmacists and a big data reward from its efforts during the pandemic. The chain requires people who sign up for COVID-19 vaccine appointments to create a myWalgreens account, and in its second quarter of 2021, membership was up 41 percent from the previous quarter, reaching roughly 56 million people, company leaders said on an earnings call at the end of March.

The company’s Find Care platform, which connects patients to telehealth providers, benefits enrollment and health care services, also saw about 70 million visits in the second quarter, mostly driven by searches for COVID-19 vaccines and testing.

“These companies are trying to serve as the platform, not necessarily offer all of the services themselves, but be the hub through which consumers go to find what they need in health care,” said Dan Clarin, a managing director at consulting firm Kaufman Hall & Associates LLC, who previously worked at Walgreens. Walgreens declined to make executives available for an interview.

Walgreens is also on track to open 40 Village Medical at Walgreens sites, which offer primary care in drugstores, by the end of the summer, and is looking to automate part of its pharmacy operations to allow pharmacists to spend more time on patients’ health needs.

“The importance of the pharmacy providing health care in the local community, both in physical locations and through our digital platforms, is greater than ever,” Alex Gourlay, the company’s co-chief operating officer, said on the March 31 earnings call.

Walmart’s efforts provide a look at how a company newer to the health care space is moving forward. It’s also advancing its in-person and digital health offerings, opening 20 health centers, mostly in Georgia, that offer primary, diagnostic and mental health care.

During the pandemic, Walmart launched pharmacy curbside delivery, began selling Medicare health plans and acquired CareZone, a startup that helps people manage their medications via an app, Marilee McInnis, who leads communications for the company’s health and wellness division, said in an email.

“The pandemic reinforced the importance of health care to our customers and communities and we led in multiple ways,” McInnis said.

There are challenges ahead: CVS and Walgreens each have thousands of clinics in communities across the country, while Walmart has reportedly slowed its plans to open more health centers. But the retailer could end up just as competitive in the long run, Beem said.

“When you look at where the health care spend is, where the chronic conditions are, their geographic footprint happens to be squarely where Walmart is,” Beem said.

The retailers’ efforts during the COVID-19 pandemic should have traditional health care providers worried, Clarin said, because while they’ve been laying the groundwork since they began offering flu shots more than a decade ago, “the scale and the speed of it is new and different.”

CVS, for example, is pushing forward with a cancer care program it launched through insurer Aetna, which the company merged with in 2018.

Shifting more health services to drugstore clinics could erode traditional health systems’ relationships with patients and force them to meet new expectations from patients, Clarin said. Outpatient volumes were up but hospital outlooks were mixed in March, according to a Kaufman Hall analysis, and part of the issue may be that patients are more open to seeking care elsewhere, Clarin said.

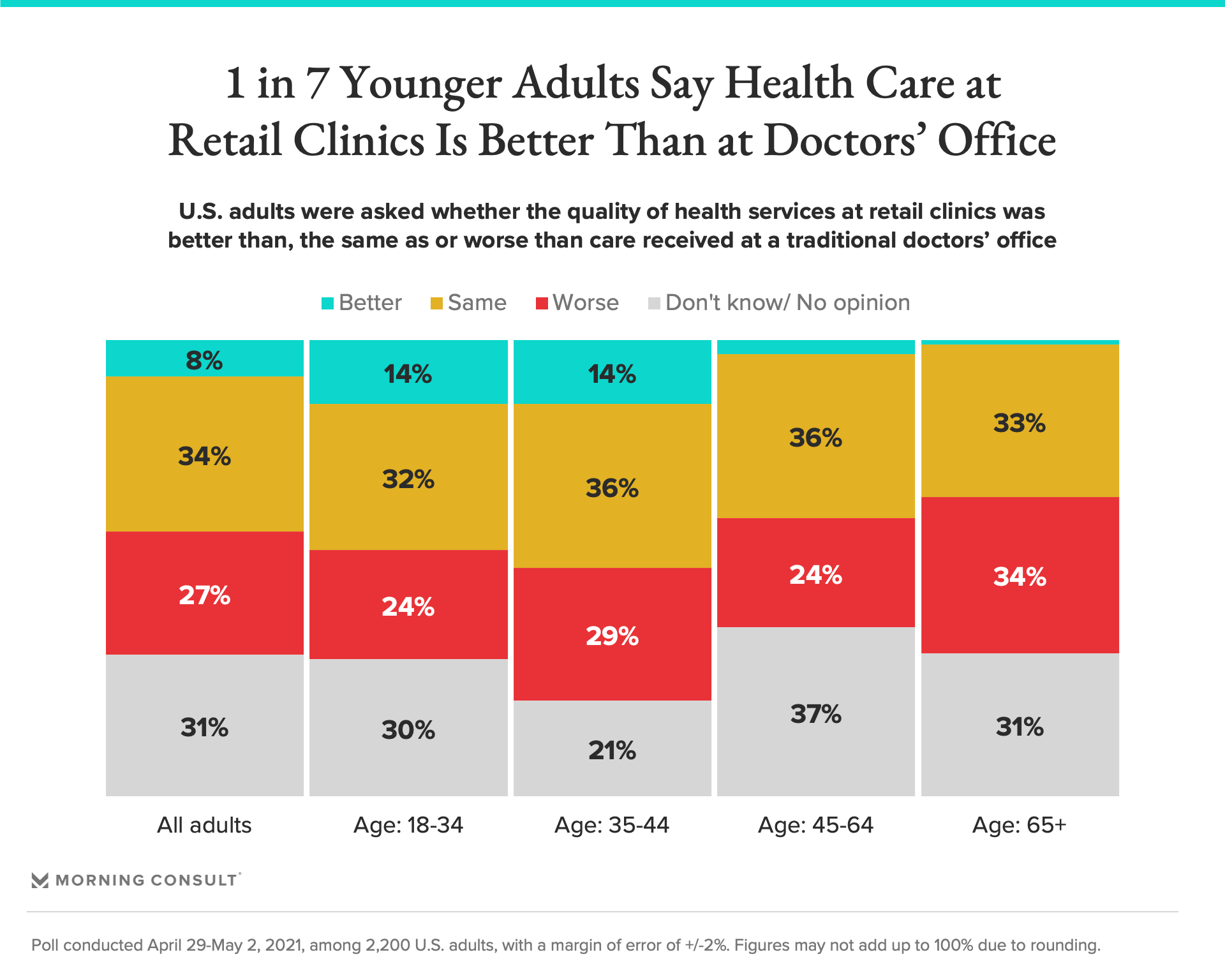

In the Morning Consult survey, conducted April 29-May 2 among 2,200 U.S. adults, 42 percent said they thought the quality of health care services at a retail clinic was either the same or better than the quality of care at a traditional doctors’ office, while another 27 percent said they thought care quality was worse at retail clinics.

Among people who had visited retail clinics during the pandemic, 58 percent said the quality of care was better or the same as the traditional physician setting, while 25 percent said it was worse. The survey carries a margin of error of 2 percentage points.

“Tomorrow, people are not going to go get knee surgery at CVS,” Clarin said. “But I think there's still this risk that all of these interactions that could have happened with a traditional provider of health care are happening somewhere else.”

Retail clinics will be dealing with the same threats, given they’re not only competing with traditional providers, but also digital-first health care entrants like Amazon.com Inc., which is preparing to expand its health care offerings in 17 additional states.

Even so, Beem said it’s unlikely that any of these players will completely upend the health care industry; rather, they’ll compete for slices of the pie, and some may usher in new modes of health care delivery. That still means health care could look very different from the patient perspective.

“You're going to have this gradual evolution away from the four walls in a physician's office, then the four walls of a primary care clinic within a retail pharmacy, into the four walls of your own home,” Beem said.

Gaby Galvin previously worked at Morning Consult as a reporter covering health.

Related content

As Yoon Visits White House, Public Opinion Headwinds Are Swirling at Home

The Salience of Abortion Rights, Which Helped Democrats Mightily in 2022, Has Started to Fade