To Weigh the Chances of a Third Party, Look to the 2016 Voters Who Feel Adrift

Coming off an election featuring the two most unpopular presidential candidates in modern history, a significant portion of the voters who actually showed up to the polls are drifting further away from the country’s two major political parties -- spelling trouble for both parties as they look toward 2020.

Antipathy about the Republican and Democratic parties is not a new phenomenon. Voters have grown more likely to eschew the labels, especially in the 21st century, and embrace the “independent” moniker. It’s a trend that’s occasionally revived the argument that the time is ripe for the formation of a third major political party.

Morning Consult’s analysis of a survey of nearly 20,000 registered voters conducted at the start of the 2020 presidential cycle shows that while data shows significant appetite -- even among those that identify with two of the major parties -- for the formation of such a party, those findings are essentially red herrings.

“The key factor is the strength of party identification,” said Stephen K. Medvic, a professor of government and program chair of public policy at Franklin & Marshall College. “People whose strength of party identification is low or nonexistent are much more likely to vote for a third-party candidate if one is available. The problem is those people are less likely to vote in general.”

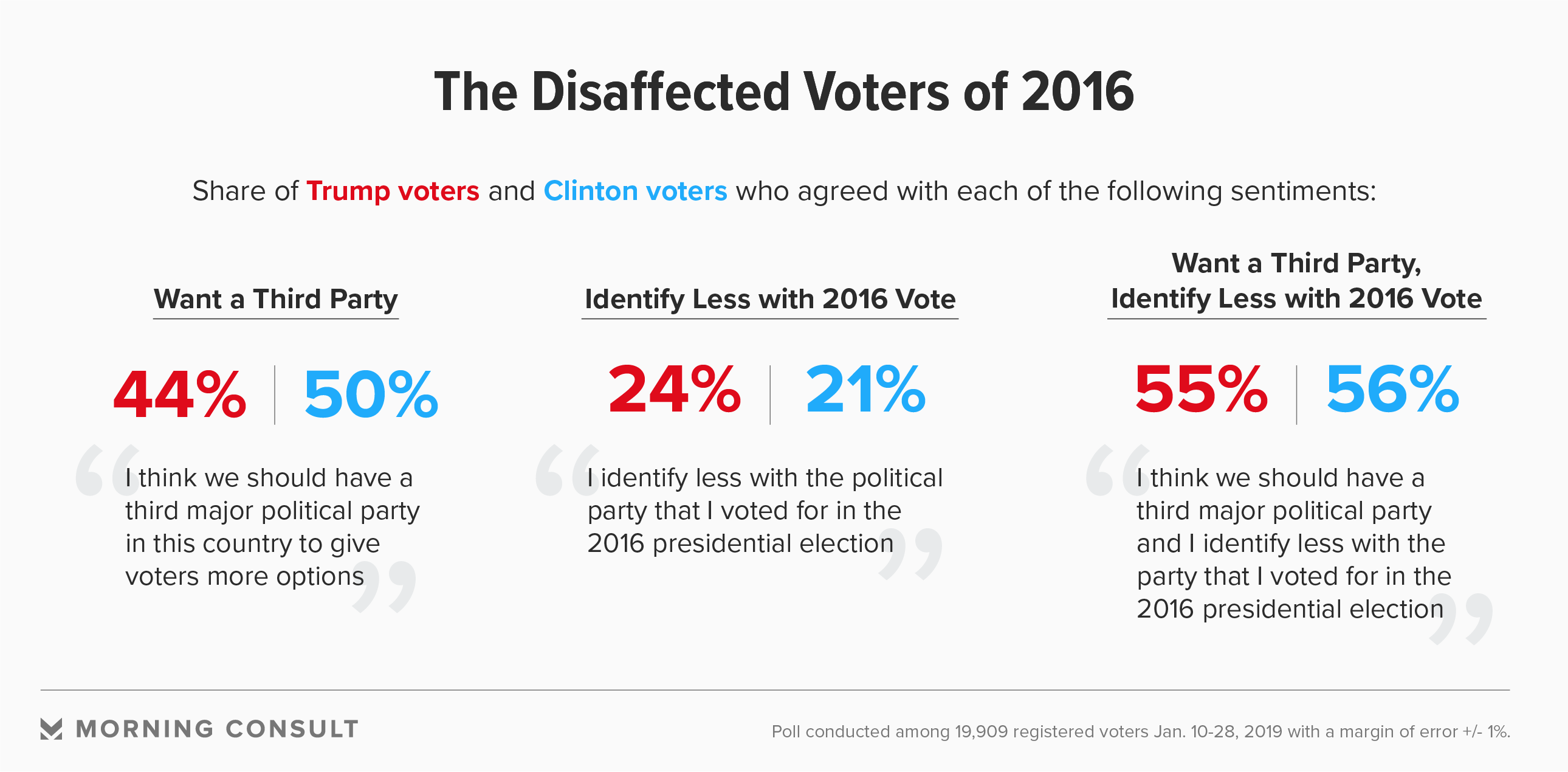

"Disaffected” voters, or those in the survey who said they identified less with the party they backed at the top of the ticket in 2016, are a more important bloc than those expressing interest in a third party, experts said -- and the survey shows Trump voters are more likely to fall under that classification.

A quarter of respondents who voted for Trump in the most recent presidential election said they identify less with the party they voted for in 2016, compared with one-fifth of the Americans who cast their ballots for Democrat Hillary Clinton. (Small shares of both parties cast votes for the other party’s candidate: Five percent of Democrats voted for Trump and 3 percent of Republicans voted for Clinton.)

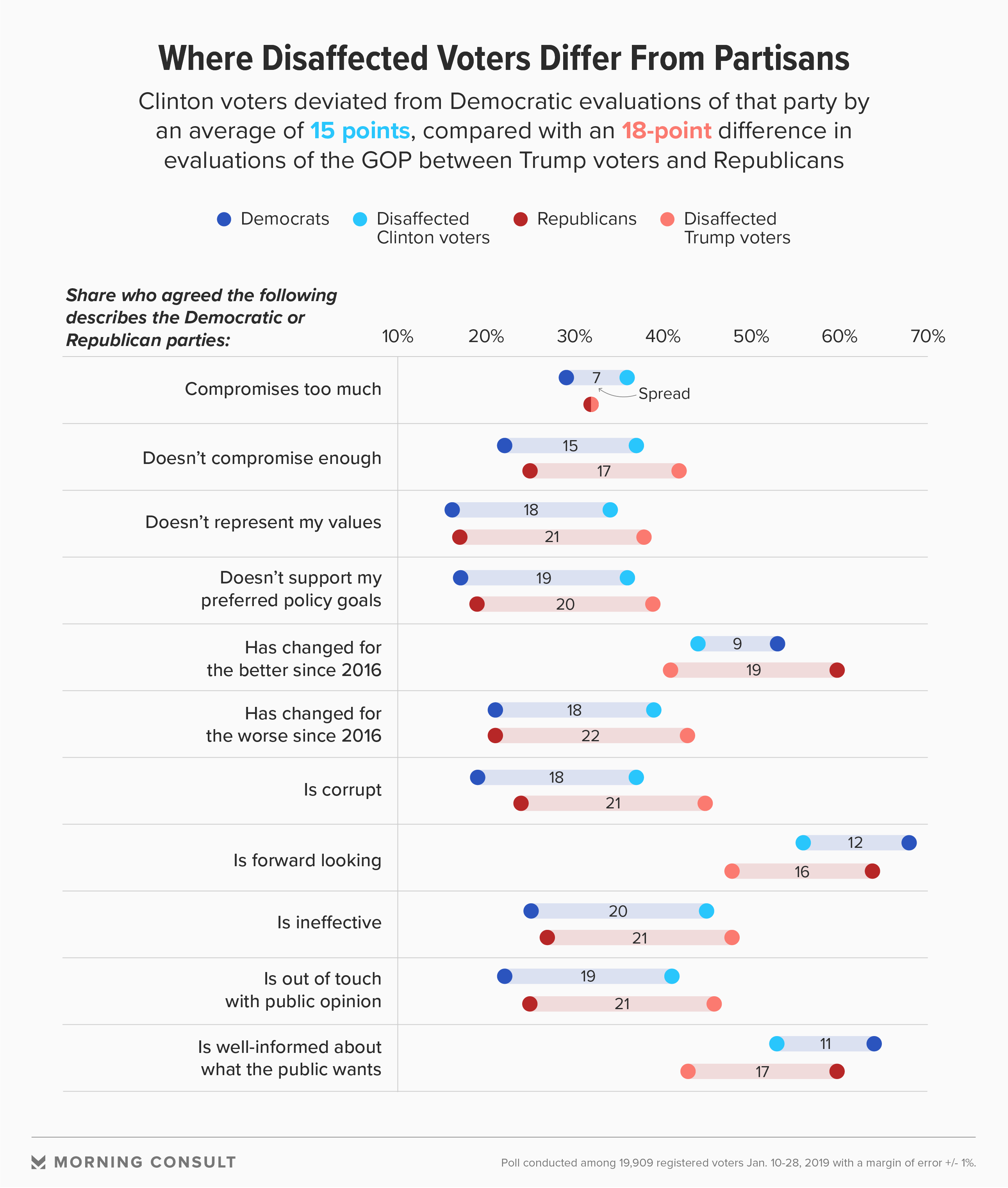

Republicans or Democrats who said the country would benefit from the creation of a third major political party had views of their own parties similar to those of the average party member.

Disaffected voters, on the other hand, were more likely than third-party supporters to deviate from rank-and-file partisans from each party -- with Trump voters slightly more out of step with Republicans.

The best predictor of a third party’s influence on an election is not how a voter feels about the third party, said Ron Rapoport, a professor emeritus of government at The College of William & Mary.

What is more important, he said, is “whether there is a difference in your evaluation between the major parties,” or distance between your own views and that of the two major political parties.

Disaffected Clinton voters were more likely than Democrats overall to say the Democratic Party compromises too much, while disaffected Trump voters were more likely than GOP voters to say the Republican Party doesn’t compromise enough.

Questions on the direction of the party did not result in a huge gap between Democrats and disaffected Clinton voters, but it did for Republicans and disaffected Trump voters -- not because of voter pessimism, but because Republicans were more likely than Democrats to say their party had improved.

Similarly, nearly equal shares from each party agreed that their side was well-informed about the public’s needs -- but disaffected Clinton voters were 10 points more likely than Trump voters to agree that the party they voted for in 2016 knows what the public wants. The Jan. 10-Jan. 28 survey had a margin of error of 1 percent.

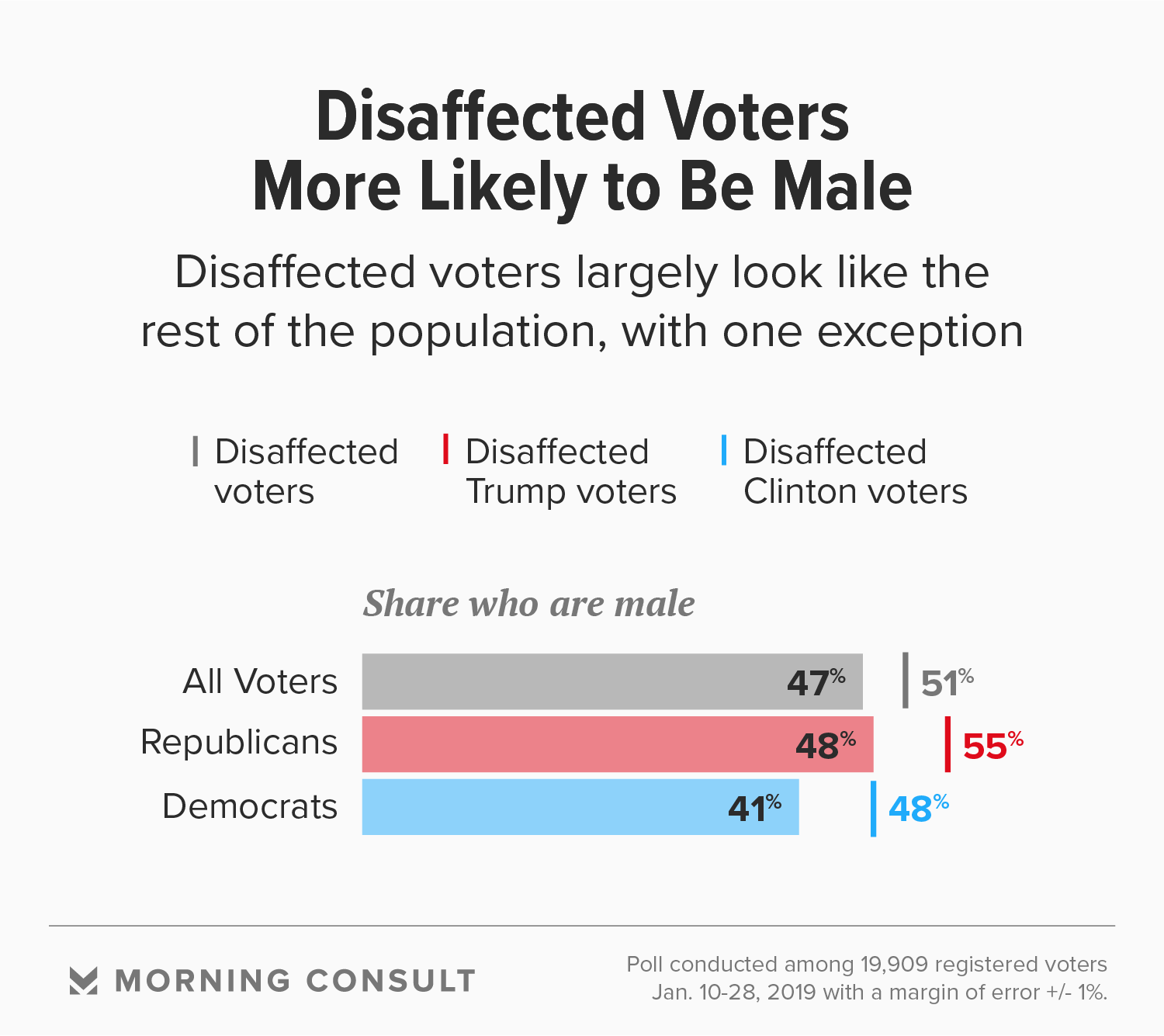

While disaffected Trump voters’ attitudes on their respective parties differed from those of Republicans, and the same for disaffected Clinton voters and Democrats, disaffected voters tend to demographically resemble the group from which they feel estranged -- except that the disaffected voter bloc tends to have a greater percentage of men.

Growing dissatisfaction with the two major political parties comes at a time of intense polarization. For a third-party or independent candidate to be successful, experts said, they would need to carve out an ideological space to attract ample support.

Despite featuring no significant success from third-party candidates, the 2016 election and the platforms pushed by Trump and Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) serve as a case in point, said Daniel P. Franklin, an associate professor of political scientist at Georgia State University. Sanders leaned into socialism; Trump emphasized immigration and trade.

Former Starbucks Corp. Chief Executive Howard Schultz, who is flirting with an independent run, hasn’t outlined much in terms of policy proposals, but he has signaled a focus on meshing conservative fiscal policy -- such as tackling the debt and reining in spending -- with a more liberal view on social issues.

Political science suggests there’s a relatively small market for such a platform, but Franklin and others said a Schultz run on those values would pose a bigger problem for Trump than for a Democratic candidate.

“If it hurts anybody, it’s going to hurt the Republicans,” said Franklin. “Because the real whipsawed voters this election are moderate Republicans.”

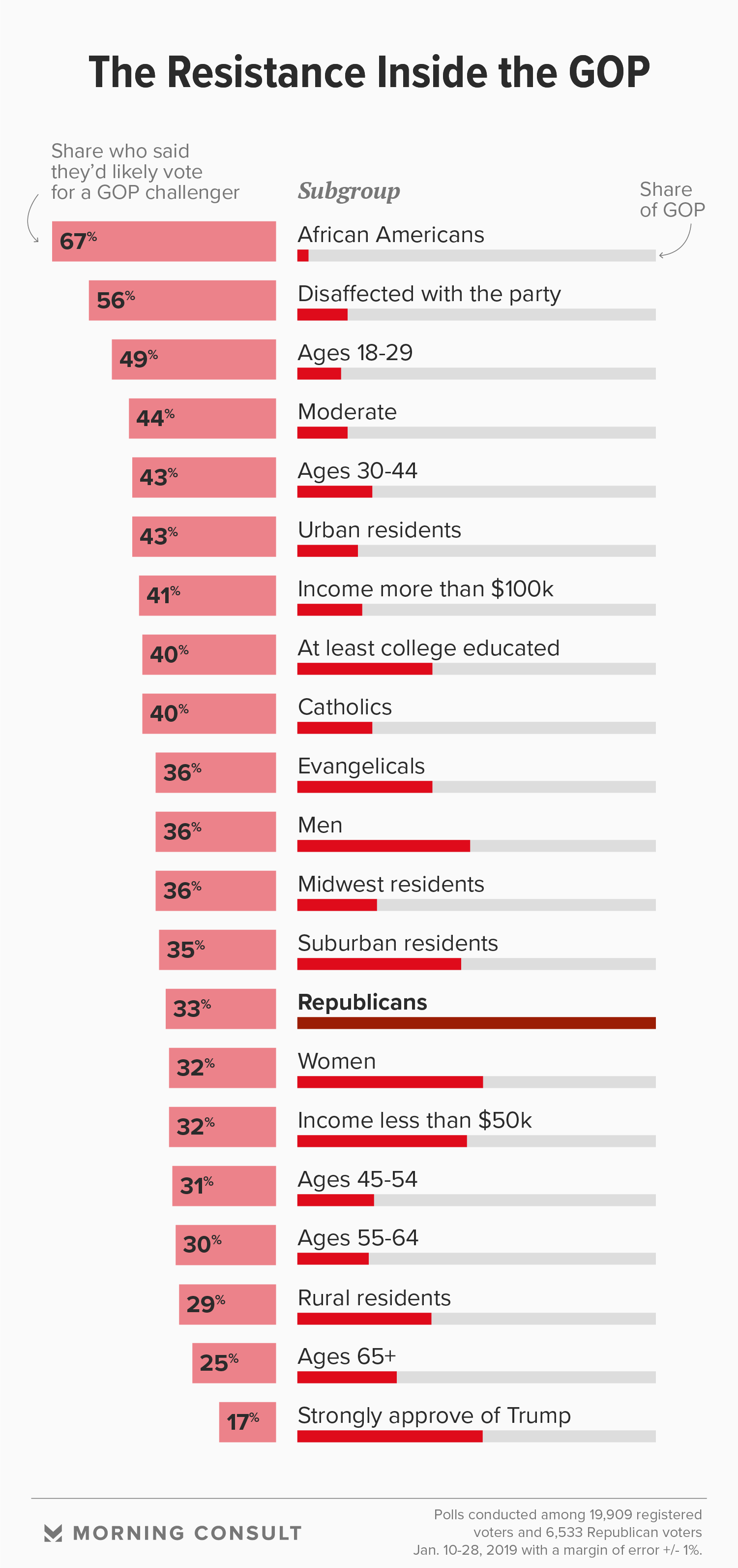

Self-described moderate Republicans were 33 percent more likely than the all GOP voters to say they’d vote for a primary challenger to Trump. The survey also shows warning signs for Trump regarding Republicans overall.

Fourteen percent of Republicans polled in the survey said they identified less with the party than they did in 2016, and 56 percent of those voters said they’d be likely to vote for a primary challenger to Trump.

“There may be some room” for a challenge to Trump from inside the party, Medvic said, but he noted that there are few principals within the GOP today who wield the influence necessary to both mount an insurgent campaign and reunite the base when the dust settles.

But the fact that some room exists, Medvic said, underscores Trump’s potential vulnerability and serves as a warning sign for could spell trouble for his general-election prospects.

And while the political world will spend a significant amount of time going over the 2016 election and how its voters are feeling ahead of 2020, experts said Americans who either couldn’t vote or sat out the last presidential cycle are likely to have a decisive influence next year.

“What makes this cycle different is that if President Trump has done anything, it’s really energize a lot of new voters,” said Franklin.

See crosstabs for Republicans, independents and Democrats, along with voters who want a third party, disaffected voters, disaffected Trump voters and disaffected Clinton voters.

Cameron Easley is Morning Consult’s head of political and economic analysis. He has led Morning Consult's coverage of politics and elections since 2016, and his work has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, Politico, Axios, FiveThirtyEight and on Fox News, CNN and MSNBC. Cameron joined Morning Consult from Roll Call, where he was managing editor. He graduated from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Follow him on Twitter @cameron_easley. Interested in connecting with Cameron to discuss his analysis or for a media engagement or speaking opportunity? Email [email protected].

Joanna Piacenza leads Industry Analysis at Morning Consult. Prior to joining Morning Consult, she was an editor at the Public Religion Research Institute, conducting research at the intersection of religion, culture and public policy. Joanna graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Madison with a bachelor’s degree in journalism and mass communications and holds a master’s degree in religious studies from the University of Colorado Boulder. For speaking opportunities and booking requests, please email [email protected].

Related content

As Yoon Visits White House, Public Opinion Headwinds Are Swirling at Home

The Salience of Abortion Rights, Which Helped Democrats Mightily in 2022, Has Started to Fade